Did ancient Sumerians observe and record the impact of the Aten asteroid over 5,000 years ago?

For over 150 years scientists have tried to solve the mystery of a controversial cuneiform clay tablet that indicates the so-called Köfel’s impact event was observed in ancient times.

Did ancient Sumerians observe and record the impact of the Aten asteroid over 5,000 years ago?

For over 150 years scientists have tried to solve the mystery of a controversial cuneiform clay tablet that indicates the so-called Köfel’s impact event was observed in ancient times.

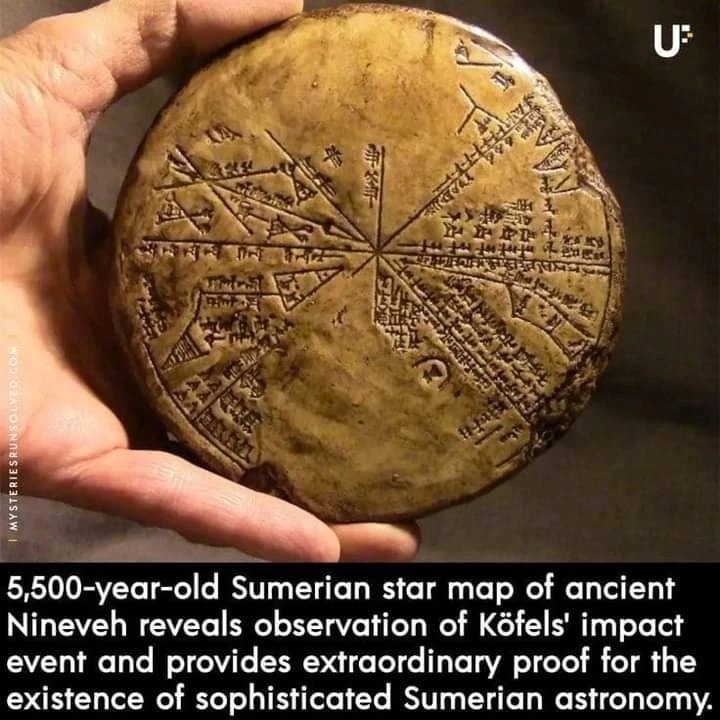

The Sumerian star map shows people observing and recording Köfels’ impact more than 5,500 years ago.

The circular stone-cast tablet was recovered from the 650 BC underground library of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, Iraq in the late 19th century. Long thought to be an Assyrian tablet, computer analysis has matched it with the sky above Mesopotamia in 3300 BC and proves it to be of much more ancient Sumerian origin.

The tablet is an “Astrolabe,” the earliest known astronomical instrument. It consists of a segmented, disk-shaped star chart with marked units of angle measure inscribed upon the rim.

Unfortunately, considerable parts of the planisphere on this tablet are missing (approximately 40%), damage which dates to the sacking of Nineveh. The reverse of the tablet is not inscribed.

Still, under study by modern scholars, the cuneiform tablet in the British Museum collection No K8538 (known as “the Planisphere”) provides extraordinary proof for the existence of sophisticated Sumerian astronomy.

In 2008 two authors, Alan Bond and Mark Hempsell published a book about the tablet called “A Sumerian Observation of the Kofels’ Impact Event”.

Raising a storm in archaeological circles, they re-translated the cuneiform text and assert the tablet records an ancient asteroid strike, the Köfels’ Impact, which struck Austria sometime around 3100 BC.

The giant landslide centered at Köfels in Austria is 500 m thick and five kilometers in diameter and has long been a mystery since geologists first looked at it in the 19th century.

The conclusion drawn by research in the middle 20th century was that it must be due to a very large meteor impact because of the evidence of crushing pressures and explosions.

But this view lost favor as a much better understanding of impact sites developed in the late 20th century.

In the case of Köfels there is no crater, so to modern eyes, it does not look as an impact site should look. However, the evidence that puzzled the earlier researchers remains unexplained by the view that it is just another landslide.

So what is the connection between the sophisticated Sumerian star chart discovered in the underground library in Nineveh and the mysterious impact that took place in Austria?

Examination of the clay tablet reveals that it is an astronomical work as it has drawings of constellations on it and the text has known constellation names. It has attracted a lot of attention but in over a hundred years nobody has come up with a convincing explanation as to what it is.

The Sumerian star map shows people observed and recorded Köfels’ impact more than 5,500 years ago.

With modern computer programs that can simulate trajectories and reconstruct the night sky thousands of years ago, the researchers have established what the Planisphere tablet refers to. It is a copy of the night notebook of a Sumerian astronomer as he records the events in the sky before dawn on 29 June 3123 BC (Julian calendar).

Half the tablet records planet positions and cloud cover, the same as any other night, but the other half of the tablet records an object large enough for its shape to be noted even though it is still in space.

The astronomers made an accurate note of its trajectory relative to the stars, which to an error better than one degree is consistent with an impact at Köfels.

The observation suggests the asteroid is over a kilometer in diameter and the original orbit about the Sun was an Aten type, a class of asteroid that orbit close to the earth, that is resonant with the Earth’s orbit.

This trajectory explains why there is no crater at Köfels. The incoming angle was very low (six degrees) and means the asteroid clipped a mountain called Gamskogel above the town of Längenfeld, 11 kilometers from Köfels, and this caused the asteroid to explode before it reached its final impact point. As it traveled down the valley it became a fireball, around five kilometers in diameter (the size of the landslide).

Around 700 BC an Assyrian scribe in the Royal Place at Nineveh made a copy of one of the most important documents in the royal collection.

Two and a half thousand years later it was found by Henry Layard in the remains of the palace library. It ended up in the British Museum’s cuneiform clay tablet collection as catalog No. K8538 (also called “the Planisphere”), where it has puzzled scholars for over a hundred and fifty years. In this monograph, Bond and Hempsell provide the first comprehensive translation of the tablet, showing it to be a contemporary Sumerian observation of an Aten asteroid over a kilometer in diameter that impacted Köfels in Austria in the early morning of 29th June 3123 BC.

When it hit Köfels it created enormous pressures that pulverized the rock and caused the landslide but because it was no longer a solid object it did not create a classic impact crater.

Mark Hempsell, discussing the Köfels event, said: “Another conclusion can be made from the trajectory. The back plume from the explosion (the mushroom cloud) would be bent over the Mediterranean Sea re-entering the atmosphere over the Levant, Sinai, and Northern Egypt.

“The ground heating though very short would be enough to ignite any flammable material – including human hair and clothes. It is probable more people died under the plume than in the Alps due to the impact blast.”

In other words, the remarkable ancient star map shows that the Sumerians made an observation of an Aten asteroid over a kilometer in diameter that impacted Köfels in Austria in the early morning of 29th June 3123 BC.