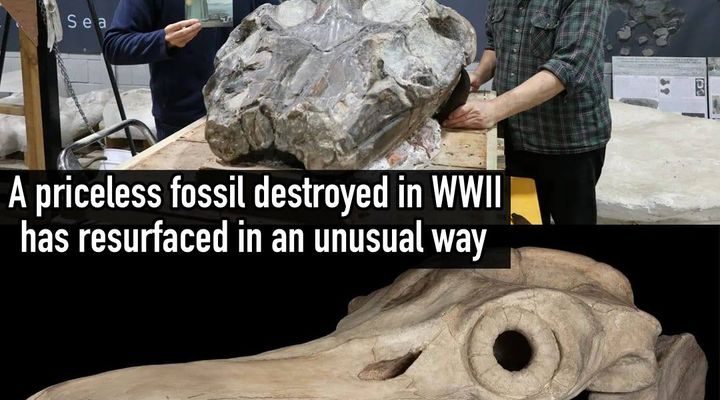

The first complete skeleton of a prehistoric marine reptile was thought to be lost forever in a bombing raid in London in 1941.

Paleontologist Mary Anning discovered the ichthyosaur fossil in 1818, two decades before the word dinosaur was even part of our lexicon.

The ancient marine reptiles got the name ichthyosaur, or “fish lizard,” because these odd-looking creatures resembled a cross between the two. Anning’s fossil was dated between 190 million to 195 million years old.

“The original fossil was highly significant in being the very first complete skeleton of any prehistoric reptile fossil ever found at the time,” said Dr. Dean Lomax, paleontologist and visiting scientist at the University of Manchester.

While the actual bones are long gone, a chance discovery has resurrected Anning’s famous fossil.

Two plaster casts were made of the skeleton. But without a record being made, the casts were kept under wraps until two scientists stumbled upon them in recent years in unlikely places: New Haven, Connecticut, and Berlin.

Anning grew up Lyme Regis, England, part of what is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site called the Jurassic Coast, where fossil discoveries are still made today. Anning and her older brother, Joseph, scoured the shoreline for fossils as children.

The scientific community first learned of Anning’s first complete ichthyosaur skeleton, called a Proteosaurus at the time, in 1819 when British surgeon Sir Everard Home studied it and published his findings. Locals had thought it was a monster and scientists a crocodile.

“This was at the point where the science of palaeontology was in its infancy, and this find, among others, really sparked a wide-spread interest in studying these remarkable fossils,” said Lomax, coauthor of a study on the casts’ discovery, via email. “Her many finds continued to add numerous pieces to the gigantic prehistoric jigsaw puzzle, which had started to come together during the early 19th century.”

Lt. Col. Thomas James Birch, an avid fossil collector, acquired the fossil from Anning and sold it to the Royal College of Surgeons in London in 1820, with the hopes of raising money for Anning and her struggling family. The fossil was still at the college when the air raid destroyed it during World War II.

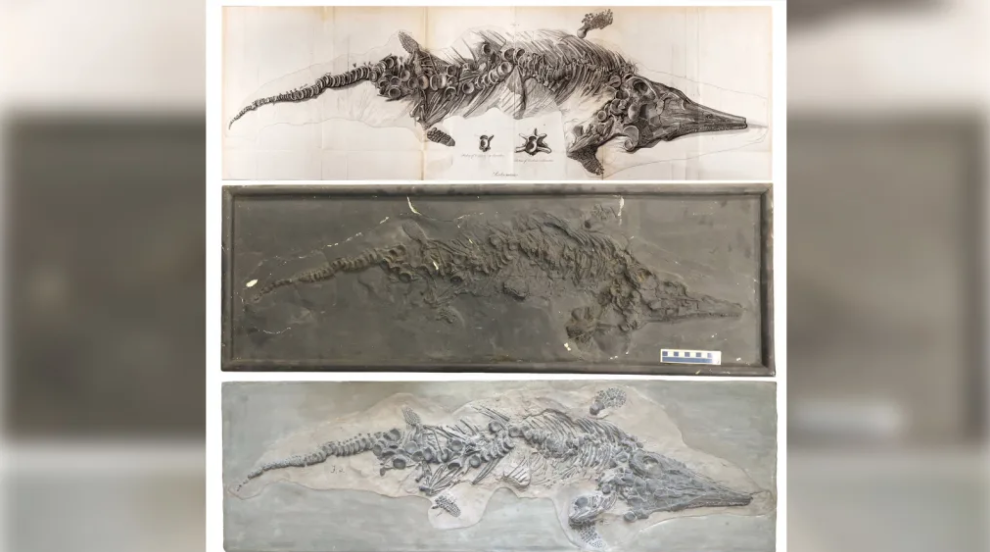

The only remaining record of the fossil was an original illustration from 1819 — or so scientists thought.

Lomax and Judy Massare, professor emerita at the State University of New York at Brockport, made their first discovery of a cast on a research trip at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University in 2016.

“Peabody curatorial staff assumed that the specimen was a real ichthyosaur fossil and not a plaster cast painted to look like the original fossil” from which it was molded, said Daniel Brinkman, museum assistant in vertebrate paleontology at the Yale Peabody Museum, in a statement.

The staff knew a Yale professor, Charles Schuchert, had purchased the specimen from the estate of Frederick A. Braun, a professional collector and dealer. Schuchert donated it to the Peabody in 1930, but there was no record of who made the cast or when, or the details of Braun’s acquisition of the cast.

Lomax and Massare found a match when they compared the cast with the 1819 illustration.

In 2019, the duo came across a second cast at Berlin’s Natural History Museum. After studying the Yale cast in detail, Lomax said he “immediately knew what it was, and I had a huge grin on my face.”

The Berlin cast was in better condition. The researchers believe it’s because the two casts were made at different times, and the Yale cast is older.

“When Dr. Lomax visited our collections, he kept asking me for information about this cast and I couldn’t help him very much because of missing records and (labeling) of the specimen,” said Dr. Daniela Schwarz, scientific head of the collection of fossil reptiles at the Berlin museum, in a statement.

“So when I learned about the outcome of his detective work and that this important specimen’s cast now rested in our collections for more than a century, I was really stunned! This discovery once more demonstrates the necessity to carefully preserve also undetermined and casted material in a natural history collection for centuries, because in the end, there will always be someone who discovers its scientific value!”

The Berlin cast was also a match with the 1819 illustration.

“Now, having two casts, we can verify the reliability of the original illustration by comparison with the casts,” Massare said in a news release. “We have identified a couple of bones that Home missed, and found a few discrepancies between the drawing and the casts.”

A study by Lomax and Massare describing the casts and their importance published Tuesday in the journal Royal Society Open Science. It’s one of the journals of The Royal Society, which also published the first paper on the skeleton’s discovery in 1819.

Lomax and Massare have found other examples of casts in museum collections that have remained hidden, losing their significance over time.

“We hope that our discovery of these two casts might encourage curators and researchers to take a closer look at old casts in museum collections,” Massare said.

Just because casts are unidentified doesn’t mean they aren’t important, Lomax said. Instead, they highlight why museums are so crucial.

“When you visit a museum collection, you never quite know what you might find,” said Lomax, author of “Locked in Time: Animal Behavior Unearthed in 50 Extraordinary Fossils.”

In the meantime, Lomax is dedicating his time to studying the Rutland Sea Dragon, the most complete skeleton of a large ichthyosaur found in the UK, measuring 32.8 feet (10 meters) long.

Anning has long been a hero to Lomax, and her groundbreaking work still inspires him. He and Massare named a previously undiscovered species of ichthyosaur after Anning in 2015, known as Ichthyosaurus anningae.

“Mary was a real pioneering palaeontologist whose discoveries genuinely changed the world,” Lomax said. “Her knowledge was superior to anybody working on these fossils at the time and she was the expert of her day.”