It is no secret that the ancient Egyptians left a lasting and impressive heritage. The relics of their time dot the world and are marveled by many – from the pyramids to the mummies, from imposing statues all the way to the hieroglyphics. But did you also know that some of their ingenious inventions are still in use, all this time after? Well, it’s true, and today we are taking you to the modern-day nation of Egypt, as we explore one intriguing remnant of their ancient industry – Egyptian egg ovens.

A curious invention, these ovens are an ingenious method of hatching a great number of eggs at once, and are truly an insight into the world’s earliest poultry industries. And you know what they say – if it works, don’t change it. And that is exactly what rural Egyptian farmers of today are adhering to – they still rely on the ancient egg oven design. A design that is 2,000 years old!

Marvel of the Ancient Times – Egyptian Egg Ovens

The invention of egg ovens – a sort of an archaic incubator – was really unique for its time, and well after as well. When the peoples of Europe had no knowledge of the incubation process, and still relied on natural means for the reproduction of chickens and other poultry, the Egyptians did it on a massive scale. An interesting note to make is the fact that the use of egg ovens survived in one small region of the Nile Delta – most certainly as a surviving heirloom of ancient Egypt that struggled for survival over the ages – and succeeded.

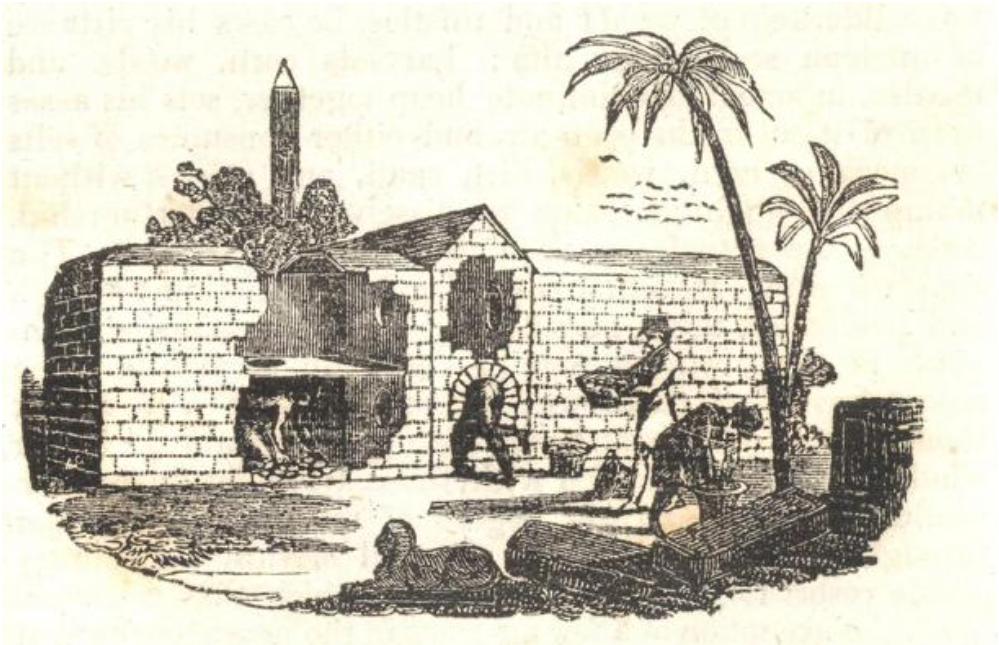

The master craftsmen and users of these ovens are centered in the village of Berme, and the small surrounding area. These oven masters are thus called bermawy in Egypt, and they have passed on their knowledge through generations. When the optimal time for hatching eggs arrives – usually the autumn – the bermawy villagers get to work. They are often hired throughout rural Egypt, where they are entrusted with a large amount of fertilized poultry eggs – perhaps gathered from entire villages.

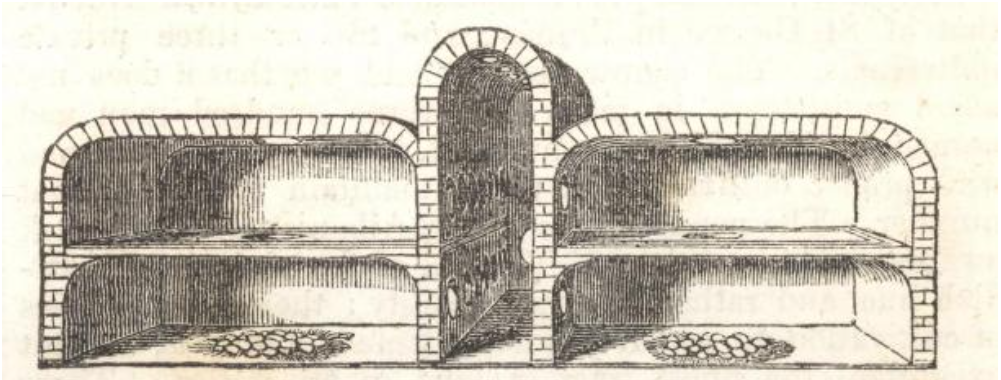

The next step is the creation of the egg ovens themselves. The Egyptian egg ovens are still very unique structures, and the craftsmen often prefer keeping the details secret to themselves. They call their ovens mamal. These structures are usually 8 to 9 feet (2.4 to 2.7 meters) high, with a central gallery that separates it in two and is roughly 3 feet (1 meter) wide. That gallery is the entrance point for the worker. Made out of brick, this structure is centered on the two rows of small chambers on each side of the gallery – the place where eggs are carefully laid on the floor. These small chambers are in two rows – one on top of the other, and have a small entrance into them.

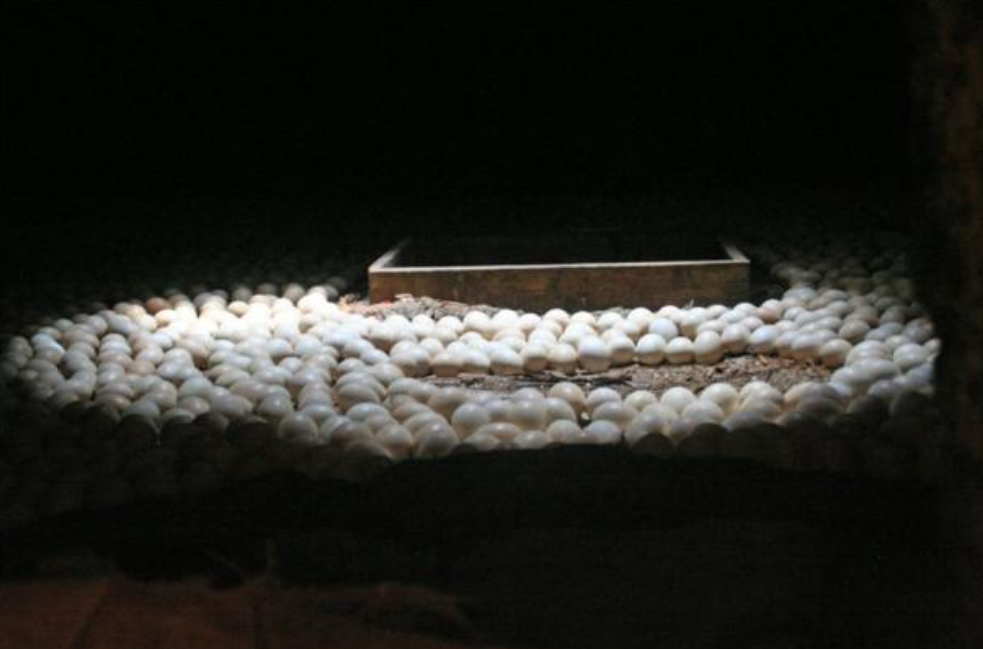

It is in these lower chambers that the bermawy workers will place up to four thousand eggs at a time. Also, the ovens often have an adjacent room where workers would reside and rest. They can access the chambers and the ‘tunnel’ from this room, in order to check up on fires and to regularly turn the eggs over – a key aspect of the hatching process. To put things into perspective, the mamal ovens can have as little as three such chambers, or as much as twelve. So, some ovens are documented that could hatch 80 thousand eggs. That is a lot of eggs.

The secret to the hatching process is – of course – heat. To simulate a broody hen, the Egyptians use fire. In the upper chambers of the oven is the so-called fire places. Each chamber, houses a small gutter fire whose heat can be transferred to the lower chamber via a small opening. The bermawy won’t use coal or wood for their fires, as those burn quick and hot, and would ruin the whole process.

Instead, to maintain a temperate heat, they always burn camel and cow dung, which is mixed with straw and then completely dried out. The central gallery – similar to a small tunnel – has holes in its roof. It is here that the smoke escapes. The whole design is precise, straightforward, and very ingenious.

An Artificial Hen – Ancient Incubators

The temperature and the intensity of the fires in the oven is carefully regulated and maintained. Too much heat too often and you kill the eggs. That is why it is important to find that optimum temperature that will closely imitate that of a brooding hen. So the oven masters keep a close watch on the open fires. If the weather is hot – as it often is in Egypt – the fires would be burning only in the mornings and in the evenings, but will be reduced to embers in between.

In colder weather, the fires can burn up to four times a day. Needless to say, it takes a lot of experience and a very keen eye to find the right temperature for the job. Moreover, when the fires are not roaring and producing smoke, the men would seal the roof openings and trap the heat inside to more effectively speed up the process.

Furthermore, the heat would naturally accumulate in the walls of the oven as bricks keep the temperature. Thus, after a certain period of roughly 10 to 12 days, the fires would no longer be kept, as the accumulated heat would be sufficient to maintain the hatching process – which in itself takes 21 days.

After the fires are gone, after those 12 days, a portion of the eggs is transferred to the upper chambers, which are cleaned from embers and ash. This helps reduce the crowding of eggs and eases hatching once it happens. Of course, as it is a part of the natural process, and also influenced by the artificial conditions, it is normal that not all eggs will hatch. It is estimated that around a ⅓ of the eggs in an oven will not hatch. Even so, the number of chicks produced in these ovens annually can be truly astounding – up to a 100,000,000 chickens can be produced each year in Egypt by use of these egg ovens.

Peculiar Skill of the Ancient Egyptians

Just how amazing this ancient invention is, can be easily understood when we consider the fact that the ancient Greeks were truly astonished by what they observed in ancient Egypt. The civilization that bloomed in the Nile Delta truly did make some milestones – advancing rapidly with papyrus making, mathematics, art, pyramids and writing systems. But there were also the egg ovens, which were no less important and amazing. Aristotle wrote of them, stating that the Egyptians hatched “great numbers of eggs” with help of dung heaps. Some two centuries after him, Diodorus Siculus also writes of them. In his work, the Library of History, he states:

“The most astonishing fact is that, by reason of their unusual application to such matters, the men (in Egypt) who have charge of poultry and geese, in addition to producing them in the natural way known to all mankind, raise them by their own hands, by virtue of a skill peculiar to them, in numbers beyond telling.”

This states that even in ancient Egypt, the mass hatching methods were in full swing, and that the sheer number of hatched birds was unlike anything the world had seen at that time.

One interesting fact leads to a number of interesting possibilities, and certainly bears further investigation. Since chicken was not an established part of the Egyptian diet, all the way up to the 4th century BC, could it be that the mass hatching system of the egg ovens was devised for a different bird, and a different purpose? A possible answer lies in the ancient Egyptian mummification practices, and specifically the god Thoth.

The Egyptian Egg Ovens Considered More Wondrous Than the Pyramids : @atlasobscura https://t.co/zojzmZhqSQ

— HTAV (@HTAVed) December 23, 2019

Hatching the Sacrifice

Thoth was an ibis-headed god, and one of the most revered deities of the ancient Egyptian pantheon. Thus, the Egyptians offered to him numerous sacrifices in form of mummified ibises. The ibis, a wild bird, was caught in wild, but when demand grew higher, it was quite possibly bred on farms as well – as numerous discoveries have proven.

To date, more than 5 million ibis mummies have been unearthed across Egypt – a number that would require a huge supply of birds, one that would surpass the natural wild cycle of reproduction. Could it be that the ancient Egyptians devised a way to gather and hatch great numbers of ibis chicks in these egg ovens? The possibility certainly exists, and the theory is not that strange to consider.

Egyptian Egg Ovens Better Than the Pyramids?

A French entomologists, Rene Antoine, visited Egypt in 1750, and observed the egg ovens in action firsthand. He later wrote that the “Egyptians should be more proud of them than of the pyramids.” To an extent, his statement is not that odd – the egg ovens were an ingenious invention, one that served a purpose and was greatly ahead of its time. On the other hand, the pyramids, however magnificent they are, were merely a symbol and had no obvious benefit to the society.

During the middle ages, the egg ovens of Egypt were something never before seen in Europe. The medieval societies lacked such a mass industry, and considering that a brooding hen can only hatch up to 15 eggs at a time, the egg ovens would certainly be something unimaginable.

That is why, in the 14th century, when an Irish friar, Simon Fitzsimmons, visited Egypt in his travels and observed the egg ovens in action, he immediately considered them astonishing, and even somewhat magical. He wrote:

“…in Cairo, outside the Gate and almost immediately to the right … there is a long narrow house in which chickens are generated by fire from hen eggs, without cocks and hens, and in such numbers that they cannot be numbered. In that house, on both sides the earth is raised to the height of an altar, and extended the whole length of the house, in which there are artificial ovens or furnaces, in which they place innumerable eggs, and around them continually night and day are fed fires for twenty-two days, usually, or twenty-three, so that all of these eggs emit chickens. They are so numerous that they are sold by the weight, like wheat, instead of individual. We saw, in public, people who sold hens and chicks, some of whom according to our estimation, had two or three thousand which they fed from the grain that fell from passing loaded camels.”

Undoubtedly this was a sight never before seen for the travelling Irish monk, and he immediately ascribed fire as the means of creation. To observe such great number of chicks was surely unbelievable, and he quickly mentions that they are sold in bulk. The concept sadly never caught up in Europe, where it would surely be a radical change. Such was the power of the ancient Egyptians, their civilization, and its heritage.

In the 21st century, one would think that the egg ovens have no more practical use. And with the modern Egyptian state, and the onset of the mass industrial incubation and chicken farms, one would think that this is true. But surprisingly, the Egyptian egg ovens are still in use to this day. In the remote rural locations of Egypt, where the modern and industrial methods are still at bay, farmers rely on the 2,000-year-old method of mass hatching.

Some minor details have changed, but the gist of it is unchanged. Often, the dung fires are replaced by more convenient petroleum lamps that can produce enough regulated heat for the hatching process. But it is still an amazing thing to consider: a 2,000-year-old invention – still in full swing, and still as useful as the first time.