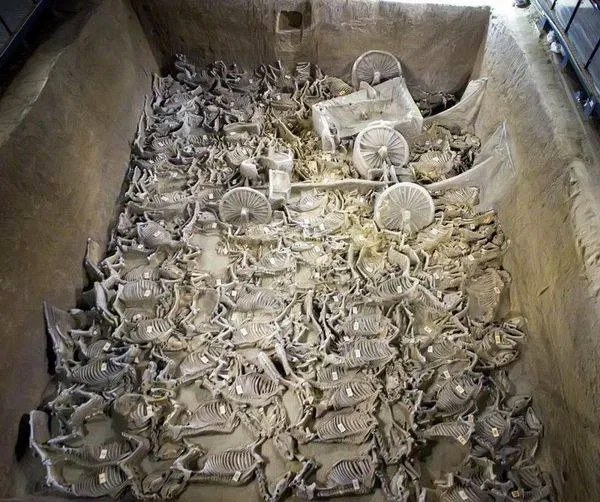

Archaeologists have found four ancient chariots and the remains of nearly 100 horses buried in a tomb in Xinzheng City, Henan province, central China. The chariots date to the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.) and one of them in particular is an exceptional example of a luxurious vehicle with all the bells and whistles of the era. It’s huge, 2.56 meters (about 8’5″) long and 1.66 meters (about 5’5″) wide, and was elegantly appointed with bronze and bone decorations. The chariot has set a new record as the largest ancient horse-drawn vehicle discovered in Xinzheng City, which is saying something because more than 3,000 tombs have been unearthed in the area, including chariot and horse burials.

Scientists believe the tomb may have belonged to a noble family of the Zheng state (806–375 BC), which was a vassal kingdom that governed this part of central China during the Zhou dynasty (1100–221 BC).

The leader of the dig, Ma Juncai, told Xinhua that no written records have so far been uncovered at the site, making it unclear who the burial pit belonged to, but archaeologists think it likely to have been the funeral site for a Zheng lord.

The site was first excavated in 2001. Two pits were revealed by the dig back then, but work was interrupted for 16 years until archaeologists were finally able to return to the location and pick up where they left off in February 2017. Over the nine months they’ve been excavating, archaeologists have unearthed the skeletal remains of more than 90 horses in addition to the four chariots. Pit 3 is the largest of the three tombs, and boy did they need the space. Dig leader and Henan Province Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology archaeologist Ma Juncai estimates there are at least 100 horses buried here, but there could well be more. She believes there are more chariots yet to be unearthed as well.

A number of bronze artifacts have also been discovered in Pit 3. Archaeologists hope a thorough study of the bronze pieces will shed new light on the technological prowess and manufacturing methods of the period. They also hope the bronze artifacts might reveal more information about who was buried in the tomb, their social status and fill in some blanks about Zheng-era funerary practices.