In the 16th and 17th centuries while, with astonishing hypocrisy, Europeans were reacting with disgust and outrage to reports of cannibalism brought back by travelers from the New World. And yet in this very period people were still treating themselves with corpse medicine, cures and remedies consisting of human blood, bones, organs, and human fat! Perhaps the most extreme of these treatments was that of ‘mellified man’ – think a 100% honey diet, death, and his fat for consumption as medicine. Not that corpse medicine was anything new or even something that only Europeans practiced!

Corpse medicine is found in ancient medical texts from India, China, Mesopotamia, and Greece. It was popular with the Romans and practically every culture around the world resorted to these gruesome practices to treat a range of ailments from coughs, headaches, palsy, vertigo and bruises to epilepsy.

Corpse Medicine 1: Mellified Man And His Honeyed Human Fat

While there was a host of grisly recipes out there, one of the most intriguing and elaborate was the mellified man, a human being mummified into honey candy, which was then used to mend broken and wounded limbs. It finds mention in Chinese medical sources, in particular in the definitive 16th-century medical encyclopedia, Bencau Gangmu by Li-Shih-chen. The remedy was not a Chinese one, however. According to Li-Shih-chen it was an ancient Arabic practice.

Eating Insects: The History of the Human Hunger for Bugs

War and Peace in Pre-Modern Europe: Have We Really Bypassed Brutality?

Making a mellified man involved an elderly male volunteer, 70 to 80 years old, who agreed to sacrifice himself for the greater good. He gave up eating anything other than honey and bathed in it every day. In time, a month or so, his insides had turned into honey and even his excretions were honey. Obviously, a diet consisting solely of honey would eventually prove fatal for reasons of oversaturation, and when that happened, the corpse medicine process began.

In the next stage, the corpse was put into a honey-filled coffin, which was then sealed and left undisturbed for a century. When the seal was broken open, the body had turned into a giant honey candied confection that was believed to have powerful healing properties.

Honey does have great anti-bacterial and antiseptic properties and was widely used in ancient medicine to treat skin disease and protect wounds from festering. This made it a great embalming fluid as well. Herodotus mentions its use for this purpose by the Assyrians. The body of Alexander the Great was supposedly submerged in honey while being transported for burial.

However, Li-Shih-chen disclaimed any first-hand experience of the practice of human mellification and admitted it was only hearsay. There is also no archaeological proof of the practice. Since he provides a recipe, though, some have speculated that the practice too must have existed. In any event, if the mellified man was only myth, proof does exist of other, extremely bizarre corpse medicine remedies that were undoubtedly widely prepared and consumed.

Corpse Medicine 2: Powdered Mummy

Powdered mummy achieved almost cult popularity in Europe from the 12th to the 17th century. It was touted as a cure for everything from headaches to stomach ulcers. Applied topically or mixed in drinks, it was said to heal bruises. The French King Francis I (1494–1547) always carried some on his person, as a safeguard against accidents. Francis Bacon had great faith in mummy powder for staunching blood flows from wounds.

Atypical Nourishment – Hematophagy, Cannibalism and Necrophagy

Human Skull ‘Cups’ and Butchered Bones Lead Archaeologists to One Conclusion – Neolithic Cannibals

There was a roaring black-market trade in mummies that led to the plunder of many Egyptian tombs. Such was the demand, however, that a trade in counterfeit varieties also flourished, with the nearest graveyard filling supply gaps.

Corpse Medicine 3: Human Blood

One such remedy that had wide currency in the western world and outlasted all others was human blood consumption. The Romans drank the blood of fallen gladiators for vigor and vitality, and as a cure for epilepsy when mixed with human liver. There are even accounts of people drinking blood straight from a gladiator’s arm and it was sold while it was still warm.

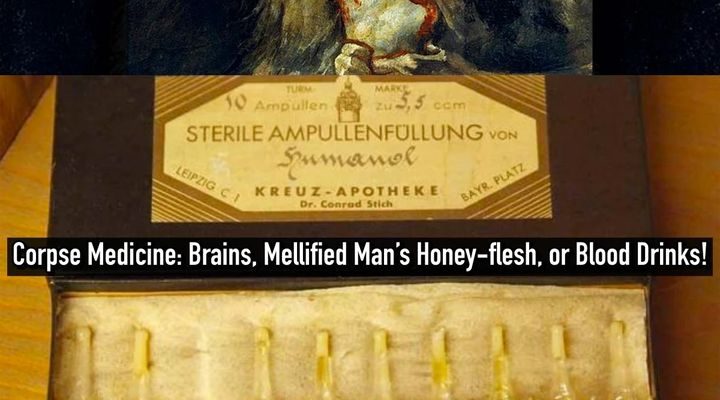

Human blood, as fresh as possible, remained a highly prized corpse medicine remedy. The 16th century Swiss physician Parcelus recommended drinking it and one of his followers went to the extreme of suggesting that it be sourced from a living body. Fresh blood procured from executions was certainly a popular source.

And if the idea of drinking raw blood turned a person’s stomach, there was a 1679 recipe from a Franciscan apothecary for blood jam. In parts of Denmark, right to the 19th century, crowds gathered below scaffolds, holding up cups to gather drops of blood from executed bodies. In 1908, the last-known attempt to drink blood at a scaffold was recorded in Germany.

Corpse Medicine 4: Powdered Human Skull Remedies

Powdered human skull formed another popular remedy. It was held to be a powerful cure for headaches. This originated in the homeopathic belief that like cures like. The remedy was brought into vogue by King Charles II of England.

Exiled in France, Charles developed an interest in chemistry. He paid Jonathan Goddard, a famous surgeon and professor at London’s Gresham College, an enormous sum for the rights to the remedy and frequently prepared it himself in his private laboratory. Made from the essence of powdered skull, these so-called “Kings drops” were said to cure headaches and promote vigor. Powdered human skull was the first thing Charles swallowed when he woke up and felt unwell on the morning of 2 February 1685, four days before he died.

The pulped brain of a young man who had died a violent death was recommended as a brain cure by some European “doctors.”

And human fat was used as a remedy for joint pain, muscle cramps, and nerve damage. To extract it, bodies of executed criminals and enemy soldiers were taken to processing labs where they were boiled. If that wasn’t gory enough, some chemists prepared even more sinister concoctions by chopping up a cadaver, mashing it to paste and then soaking and distilling it.

The Power of the Human Spirit

The reason why human remains were considered so powerful was that the human spirit was still believed to be inhabiting them. The idea of the spirit, linking body and soul, was a very pervasive one in the age of corpse medicine. That is why, blood was supposed to be such a powerful curative agent. It was said to carry the soul in the form of vaporous spirits.

By ingesting parts of dead people, one was thought to imbibe their spirit and strength. Leonardo da Vinci, for example, stated that insensate life remained in the dead and it revived once united with the stomachs of the living.

There is little scientific evidence that any of these remedies were even slightly helpful. Yet, for centuries, belief in their efficacy was extremely potent, leading to prevalence of practices that seem revolting to modern sensibilities. And the reason why they died out eventually was precisely that. It was not their inefficacy but a new refinement that caused the human body and its functions to be viewed with some distaste as a source of ingestible medicines.