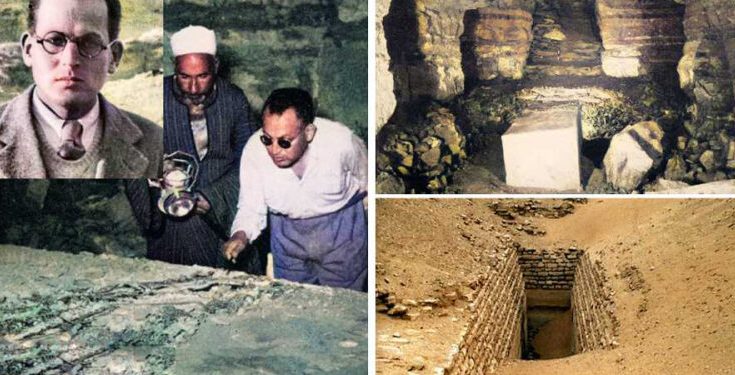

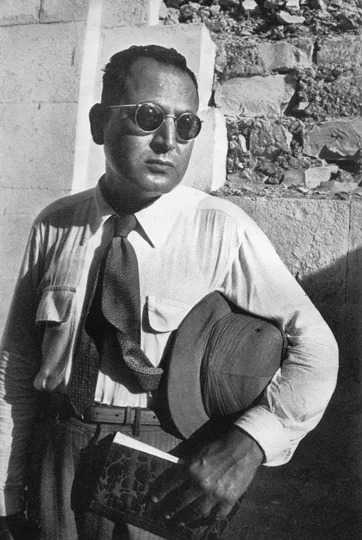

The ancient history of Egypt is filled with abundant discoveries that have not been explained. One such discovery was made by the archaeologist Zakaria Goneim in the mid-1950s. Goneim’s find was so unique that scientists are still arguing about what exactly the archaeologist found and what it was all for.

In 1951, while searching for new untouched burials, archaeologist Zakaria Ghoneim came across a wall that, in his opinion, could be one of the undiscovered, unfinished ancient pyramids. The remains of the structure were located in the necropolis of Saqqara, not far from the ancient step pyramid of Djoser, whose age is estimated to be 4,700 years old.

In his book, entitled “The Lost Pyramid” (Rinehart & Company, 1956), Goneim wrote: “It might be thought that, since the building had been used as a quarry in later times, its existence was known until a comparatively recent date. Fortunately I was able to satisfy myself that the monument had been undisturbed for at least 3,000 years and probably for longer. Proof of this lay in the large number of later burials which my workmen found during the excavations, and as the earliest of these dated from the Nineteenth Dynasty (1349-1197 B.C.), and as some were found lying undisturbed above the buried pyramid itself, it is obvious that the walls we had uncovered had not been seen by human eyes since that remote epoch.”

Since the entrance to the Egyptian pyramids is located in the middle of the northern side, finding the entrance to the unfinished pyramid was a matter of technique.

In January 1954, Goneim began his search for the pyramid entrance, certain that “no superstructure would have been built without beginning the substructure.” Excavating the northern side, he first found the remains of a mortuary temple. Encouraged, he sought the entrance there, as the entrance to Djoser’s pyramid was found in the similar location. When this proved futile, he moved the work to the north. Finally, about 75 feet from the pyramid face, he found what appeared to be the entrance gallery.

The gallery was blocked intermittently with heavy stones, and the gaps between were filled with rubble. At length, the doorway to the pyramid was uncovered. “To our extreme relief,” Goneim wrote, “we found that the doorway was intact, sealed with masonry.” The pyramid was opened on March 9, 1954.

The door led to a high gallery cut into the bedrock, but within sixty feet, they encountered a wall of rubble reaching from floor to ceiling. The team found a vertical shaft in the ceiling through which the rubble had been dropped; the mouth of the shaft above was buried in the pyramid superstructure.

Goneim determined that the shaft had not been fully breached since the pyramid was built. The blockage of rubble in the corridor proved to be more than fifteen feet thick, but first, the shaft had to be cleared so that the debris would not fall on the workers below. While clearing the shaft, a tragedy occurred that stopped the excavation for a long time. One of the stone blocks collapsed down and buried the workers, killing one. This immediately spread the tales of a pyramid curse and the media exaggerated the news, claiming that the pyramid collapsed and killed 80 people.

Then the rumor spread that an evil spirit was imprisoned in the tomb, which would destroy everyone. Goneim himself was also frightened, but he resumed the excavation. Having cleared the chamber, Goneim found many burial vessels, on the seals of which he read the name of “hitherto unknown king,” Sekhemkhet (this pharaoh had been known by another name, Djoser Tati).

Goneim also found a golden treasure: 21 golden bracelets, wrist hoops, tweezers, a golden wand in the form of a sickle, golden plates, a golden shell-powder box, and many carnelian beads.

To the chamber, they had to make their way through the fragments of stones that blocked the passage due to earthquakes. At 31 meters, they found a side passage leading to a long T-shaped corridor containing 120 empty storage rooms. And only after another 72 meters, the archaeologist found a burial chamber hidden behind protective masonry and huge stone blocks. It was in the very center of the unfinished pyramid of Sekhemkhet.

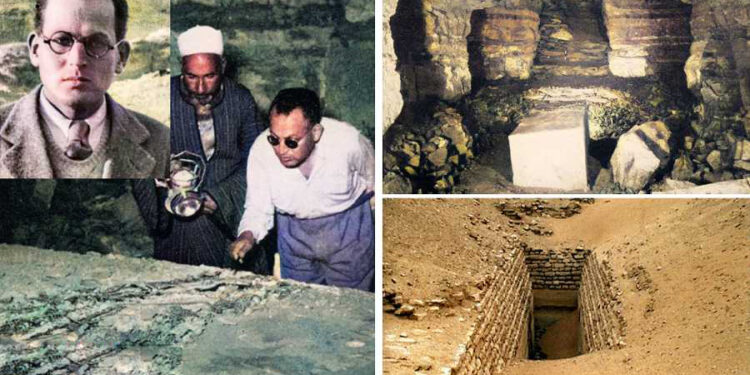

“In the middle of a rough-cut chamber lay a magnificent sarcophagus of pale, golden, translucent alabaster. We moved toward it. My first thought was: “Is it intact?” Hurriedly, with my electric torch, I examined the top for the lid. But there was no lid; the top was of one piece with the rest,” Goneim wrote.

After clearing it of sand and dust, archaeologists discovered several strange things. Firstly, on the sarcophagus in the form of the letter V was a kind of funeral wreath. Secondly, there were chips on one of the corners, which were carefully restored. And thirdly, the lid of the sarcophagus was not at the top, but at the end and went up, as if the archaeologistswere not in front of a coffin, but a trap for a wild animal.

The cement with which the lid was smeared turned out to be intact. With great difficulty, archaeologists cleared a place around the sarcophagus, installed lifting blocks, and, confident that the body of Sekhemkhet was inside, opened the “coffin”. It was empty inside. Goneim’s disappointment knew no bounds. The excavation season usually ends in April due to the heat. In the heat and stuffiness, the expedition worked until June 26 for the sake of results. And all this just to find an empty sarcophagus! The excavations were stopped.

Returning to work in 1955, Ghoneim cleared the gallery and found many artifacts, but he could not solve the riddle of the pyramid. Perhaps an evil spirit was indeed imprisoned in the sarcophagus? Soon the curse overtook Goneim: in 1959, he committed suicide by drowning himself in the Nile.

Goneim himself determined the age of the pyramid at 4700 years. But radiocarbon analysis of the “wreath” that lay on the sarcophagus showed that the plants were 800 years older than the pyramid. Why did the Egyptians stop building the pyramid? Why did they leave? Why was the sarcophagus so carefully closed and the passages laid? Why did someone put ancient dried plants on it? There are several versions of this.

The internal architecture of the pyramids still baffles experts. They have so many narrow, inclined and vertical passages that only a snake can move along. Moreover, the Egyptian god Nehebkau, the judge of the dead, could turn into a snake. In the form of a huge snake, Apep is an ancient Egyptian spirit of evil, darkness, and destruction and the arch enemy of the sun god, Ra.

In 1963, Jean-Philippe Lauer took up the excavation of Sekhemkhet’s monument by investigating the possibility of a south tomb, a feature which he had found on the southern side of Djoser’s Step Pyramid. He also wanted to reconstruct a plan of the Buried Pyramid and try to resolve the mystery of the missing mummy.

Lauer uncovered the foundations of the south tomb below a destroyed mastaba. In a corridor at the bottom of a deep shaft, he found remains of an early wooden coffin which contained the bones of a two-year old boy (a royal prince?) with some Dynasty III vessels and gold leaf fragments. The burial chamber had been looted by robbers. Lauer went on to prove Goneim’s theory that the enclosure wall of the complex had been extended. There are many theories surrounding the Buried Pyramid and its lack of completion which still remain a mystery.