At Europe’s oldest battlefield, archaeologists found new clues about who fought on the skeleton-strewn grounds some 3,250 years ago.

Starting in the 1980s, people began finding ancient daggers, knives and other weapons in the river sediment around Tollense Valley in northeastern Germany. Several skulls were found, too. In 1996, an amateur archaeologist even discovered an arm bone, pierced with an arrow, sticking out of the ground.Â

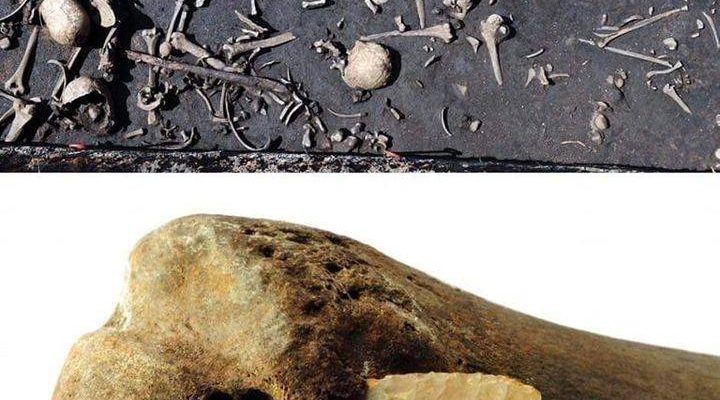

But it wasn’t until 2007 that a systematic exploration of the site began. Over the last decade, archaeologists have unearthed a veritable battlefield, dating back to 1250 B.C., spread along the banks of the Tollense River, about 75 miles (120 kilometers) north of Berlin. To date, the researchers have found the skeletons of 140 people, mostly men between the ages of 20 and 40, among the remains of military equipment and horse bones. [See Photos of the Bronze Age Battlefield]Â

Archaeologists had lacked evidence of large battlefields from the Bronze Age in Europe, despite all the metal swords, hill forts, depictions of violence and scarred human skeletons from this period. (Around the Mediterranean, this was the era of the legendary Trojan Warand Egyptian warrior kings like Ramesses II, whose tombs document his battle with the Hittites.)

Thomas Terberger, one of the German archaeologists who launched the excavation at Tollense Valley, said his team is now sure they’re looking at a true battlefield.

“We are very confident that the human remains are more or less lying in the position where they died,” Terberger, of the Lower Saxony State Office for Cultural Heritage, told Live Science.

What’s been found so far at the site probably represents only a fraction of the carnage, Terberger added, as the winning side likely looted weapons from the fallen enemies and recovered most of their dead comrades for a more respectful burial. Terberger estimated that more than 2,000 people might have been involved in the fight. [10 Epic Battles that Changed History]Â

“This is beyond the local scale of a conflict,” he said, meaning that this was likely a major battle in the region, not a fight between neighbors.

To get a clearer picture of who fought in the battle, Terberger and his colleagues decided to do a chemical analysis of the skeletons. The researchers looked for elements like strontium, a naturally occurring mineral in food that can leave a geographically specific signature in a person’s bones. (For example, someone who spent most of his or her life in Scandinavia will have a different strontium signature than a person from Spain.)

The results of the study, which were published in August in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, showed that there was a large, diverse group of nonlocals involved in the battle. Unfortunately, strontium analyses are not so exact that archaeologists “can point to a map and say, ‘They came from there,’” Terberger said.

The results do at least suggest that many of these nonlocals came from the south, perhaps from southern Germany and Central Europe. This interpretation agrees with some of the archaeological finds; Central European-style arrowheads and dress pins have been found on the battlefield and nowhere else in northern Germany, Terberger said.

At least in their chemical profile, the warriors also closely resembled the slain soldiers found in a nearby mass grave at Wittstock. That grave is much younger; it was filled in 1636 during the brutal Thirty Years War. But it could have some relevant parallels for the Bronze Age, Terberger and his colleagues argued.

From historical accounts, archaeologists know there were mercenary soldiers from all over Europe fighting at Wittstock. If the fighters in the battle at Tollense likewise had multiethnic origins, Terberger said, it might mean “these were warriors who were trained as warriors.” In other words, they were professionals,not simply villagers defending their farmsteads in a local dispute.

The archaeologists are still searching for answers to the mystery at the heart of the battle: Why was it fought? Terberger said he and his team will look for more clues in the wider landscape. The Tollense River was important for north-south trade, and there is an “amazing” concentration of valuable artifacts, like gold rings and jewelry, found in the valley, he said. What’s more, the battle took place right around a narrow part in the river where there was a wooden trackway that dates back to 1900 B.C. and was possibly a bridge connecting the two sides of the river.

“It was probably an important crossing in the landscape,” Terberger said.

This time, in 1300 B.C. was also marked by cultural upheaval in Central Europe, when new ideologies were coming in from the Mediterranean with the start of the Urnfield culture (named for the way the dead were cremated and buried in urns). “It’s not by accident that our battlefield site is dating to this period of time,” Terberger said.

Original article on Live Science.Â

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor’s degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity. Follow her on Twitter and Google+.