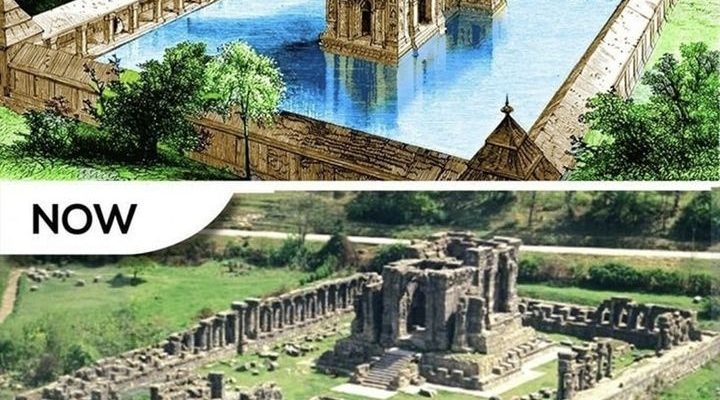

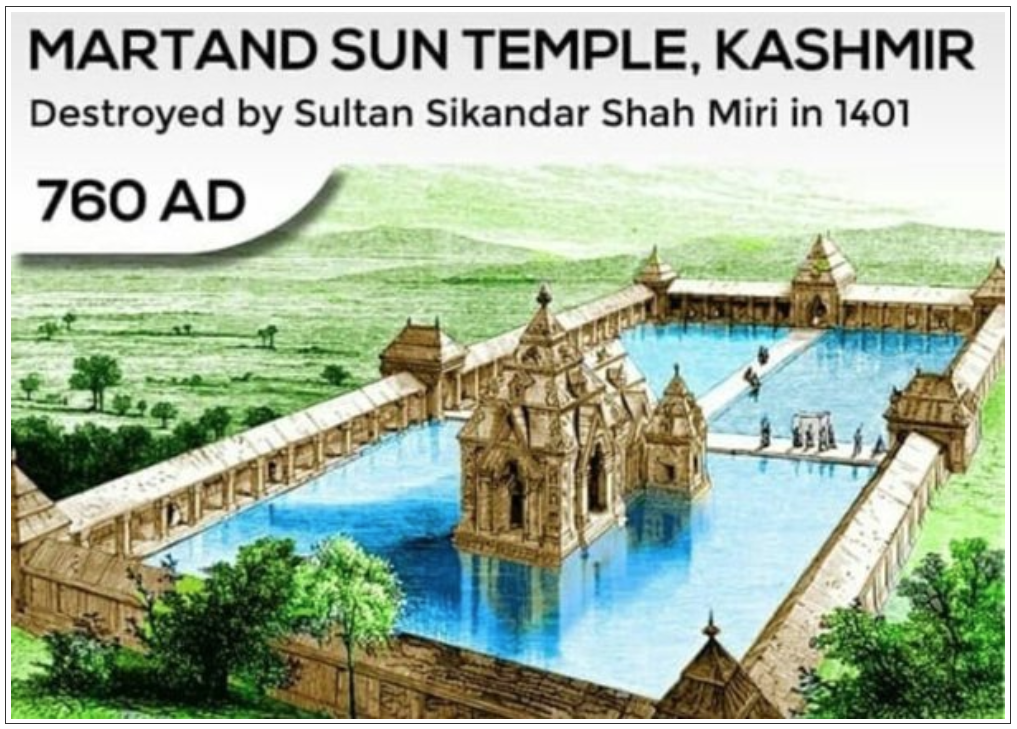

Martand Sun Temple in Kashmir. It was destroyed by Sultan Sikandar Shah Miri in 1401 AD.

Around 1200 years ago, a great king built a grand temple, dedicated to Martand, the Sun god. The temple had mighty grey stone walls, its courtyard was filled with river water that glinted and sparkled in the sun, and it had “something of the rigidity and strength of the Egyptian temple and something of the grace of Greece”.

The temple survives partially today in Jammu and Kashmir’s Anantnag and lends its name to the adjacent town, Mattan. It still makes for an impressive sight with the formidable grey walls standing stark against the blue sky, broken grey fragments strewn around the green grass. Some of the walls bear clear carvings of deities, and the beauty and symmetry of the temple are still amply evident. The temple is ringed by a row of pillars—the peristyle common in Kashmiri temple architecture.

Why is this ancient temple making news today? Who built the Martand Temple, and how was it destroyed? How did it come to have influences ranging from Grecian to North Indian? As the Martand Temple has been witness to over a thousand years of history, answers to questions hold lessons about India’s past and present.

Current controversies

In May this year, some pilgrims offered prayers inside the Martand Temple, an Archaeological Survey of India-protected (ASI) monument. Soon after, Jammu and Kashmir Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha participated in a ‘Navgrah Ashtamangalam Puja’ on the premises. The ASI objected to this, saying no permission was granted for the ceremony. Two months later, in July, another group of people entered the temple and held an hour-long prayer session.

Before that, in 2014, a song from the Bollywood movie Haider was shot here. A section of Hindus took offence to it, claiming the song, Bismil, portrayed the temple as the “den of the devil.”

History of Martand Temple

The Martand Temple was built by the Karkota dynasty king Lalitaditya Muktapida, who ruled Kashmir from 725 AD to 753 AD. Although some historians believe that an earlier temple existed here and was incorporated into Lalitaditya’s grander structure, others credit Lalitaditya entirely for it. Lalitaditya built his capital at Parihaspora, the ruins of which also survive to this day.

Talking to The Indian Express, Dr Aijaz Banday, a retired professor of Kashmir University and former director of its Centre of Central Asian Studies, says, “Dedicated to Vishnu-Surya, the Martand Temple has three distinct chambers—the mandapa, the garbhagriha, and the antralaya—probably the only three-chambered temple in Kashmir. This points to the position it enjoyed. The temple is built in a unique Kashmiri style, though it has definite Gandhar influences.”

A major historical source for Kashmir’s history remains Rajatarangini, written in the 12th century by Kalhana, and various translations of the work contain descriptions of Martand’s grandeur.

Hungarian-British archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein, in his Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, writes of the Martand Temple, “The ruins of the splendid temple of Martanda, which the king [Lalitaditya] had constructed near the Tirtha of the same name, are still the most striking object of ancient Hindu architecture in the Valley.”

Another retelling of Kalhana’s Rajatarangini is by Ranjit Sitaram Pandit—incidentally, Jawahar Lal Nehru’s brother-in-law—who writes, “The munificent king built the marvellous temple of Märtanda with massive stone walls inside encircling ramparts and a township which rejoiced in grape-vines.”

This description matches Stein’s, who says the Martand Temple had “massive walls of stone within a lofty enclosure and its town swelling with grapes.”

Historian G M D Sufi, in his book Kashir, writes, “The celebrated temple of Martanda possesses far more imposing dimensions than any other existing temple, being 63 feet long. The stone carving is very fine indeed. G T Vigne, the traveller, says: “As an isolated ruin this deserves on account of its solitary and massive grandeur to be ranked, not only as the first ruin of the kind in Kashmir but as one of the noblest amongst the architectural relics of antiquity that are to be seen in any country. Another view is that there is something of the rigidity and strength of the Egyptian temple and something of the grace of Greece.”

Sufi then adds, “Though Hindu, it differs from the usual Hindu types, and is known distinctively as Kashmirian and owes much to the influence of Gandhara… the sculptures show…a close connection with the typical Hindu work of the late Gupta period.”

A confluence of architectural style

Dr Syed Gazanfar Farooq, who holds a PhD in Kashmiri architecture from Aligarh Muslim University and now works in the J&K Education Department, tells The Indian Express, “From the ruins of the temple, it is evident that the complex originally consisted of a principle shrine at the centre of a quadrangular courtyard, flanked towards the north and south by two small structures… it appears that the central courtyard was initially filled with water supplied by a canal from river Lidar to a level which immersed almost one foot of the base of the columns.”

This courtyard was enclosed by a colonnade, which seem to have consisted of 84 pillars.

Dr Farooq says the temple walls are built of “huge blocks of evenly dressed grey limestone by making use of lime mortar.” This, he says, is remarkable, because the use of lime mortar “is encountered in north India generally after the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century”, and points to Lalitaditya employing immigrant Byzantine architects.

The temple is influenced by Classical Greco-Roman, Buddhist-Gandharan, and North Indian styles. Dr Farooq says this can be explained by Kashmir’s proximity to Gandhar, possible direct contact between Kashmir and Greece, and to architects from other empires making their way to Kashmir. Lalitaditya is known to have subjugated the king of Kannuaj, which can be one of the reasons for North Indian workers building his temple.

Today, the temple’s roof is missing. Dr Farooq says, “Alexander Cunningham [also called the father of Indian archaeology] assumes that a two-tiered pyramidal roof must have covered not only the central shrine but the other two smaller shrines in stone.”

Destruction of Martand Temple

Was the Martand Temple destroyed by the forces of bigotry, zealotry, or nature? Historians have for long engaged with this question, and while many believe Sultan Sikandar ‘Butshikan’ (iconoclast) was behind it, others blame earthquakes, faults in the temple’s masonry, and the simple passage of time in an area prone to weather excesses.

For those who hold Sikandar responsible, one of the main sources is poet-historian Jonaraja—who wrote the ‘Dvitiya’, or second, Rajatarangini while in the employment of Sikandar’s son Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (1420-1470)—though he is by no means the only one.

What historians agree on is that Sikandar, influenced greatly by the Sufi saint Sayyid Muhammad Hamadani, was on an ‘Islamification’ mission, and his rule saw the persecution of Hindus. The Sultan had been crowned when still a boy, and a lot of this persecution was carried out on the orders of his chief minister, Suhabhatta, who had converted to Islam, taking the name of Malik Saif-ud-Din. Jonaraja writes, “There was no city, no town, no village, no wood, where Suha the Turushka [Turk/Muslim] left the temples of gods unbroken.” Of the king, Jonaraja writes he broke images at the “instigations of the mlechchhas”.

Whether Sikandar destroyed specifically the Martand Temple is less certain. G M D Sufi cites, “The late Mr Brajendranath De’ (1852-1932), MA, Barat-Law, ICS, Boden Sanskrit Scholar at Oxford University in 1875, ex-Commissioner, Burdwan Division, Bengal, the painstaking translator of the Tabaqati-Akbari, wrote;- “There is a great deal in Jonaraja about the breaking of images, but I have not been able to find any mention of the demolition of the temples.”

Sufi reasons that as more people converted to Islam, the character of existing temples was changed by removing idols and making a niche toward the Ka’ba, but the temples were not necessarily brought down.

Dr Farooq says historians writing after Jonaraja have mentioned the Martand Temple.

After Jonaraja’s death, three sequels of the Rajatarangini were written, with the fourth and last, Chaturtha Rajatarangini, written by Suka.

Dr Farooq says, “We are informed by Suka’s Rajatarangini that a severe earthquake wrought havoc in Kashmir in 1554. However, the inhabitants of Vijayesvara, Martanda, and Varahakshetra did not experience fear from the earthquake due to the sanctity of these tirthas, suggesting that these shrines might have been visited by worshippers and their condition could have been fine at that time.”

Dr Farooq concludes that the temple appears to have been destroyed by “earthquakes, friable nature of the material used, frost and snow causing natural weathering, and improper fitting of stones at their joints.”

Why Harsha broke temples

Three centuries after Lalitaditya and two centuries before Sikandar existed a Hindu king known for destroying and desecrating temples: King Harsha (1089 AD to 1101 AD) of the first Lohara dynasty.

Harsha’s actions against the temples had nothing to do with religion—he was simply a profligate king who ran out of money and began looting temples for treasure and for the precious metals of the idols. However, Harsha appears to have spared the Martand Temple, where a few years before, his father had drawn his last breath.

Kalhana’s Rajatarangini by RS Pandit says, “In the village, the town or in Srinagara there was not one temple which was not despoiled of its images by the Turk king Harsha. There were, however, two puissant gods who were not insulted by him; in Srinagara the holy Ranasvämin and Martanda among the towns.”