An ancient Egyptian woman had an ovarian tumor with teeth and was buried with a possible healing object.

Teratoma with Tooth A (lower) in situ and Tooth B (upper) retrofitted in crypt. (Image credit: A. Deblauwe/Amarna Project)

While excavating an ancient Egyptian cemetery, archaeologists made a rare discovery: an ovarian tumor nestled in the pelvis of a woman who died more than three millennia ago. The tumor, a bony mass with two teeth, is the oldest known example of a teratoma, a rare type of tumor that typically occurs in ovaries or testicles.

A teratoma can be benign or malignant, according to the Cleveland Clinic, and it is usually made up of various tissues, such as muscle, hair, teeth or bone. Teratomas can cause pain and swelling and, if they rupture, can lead to infection. In the present day, removal of the mass is the typical treatment.

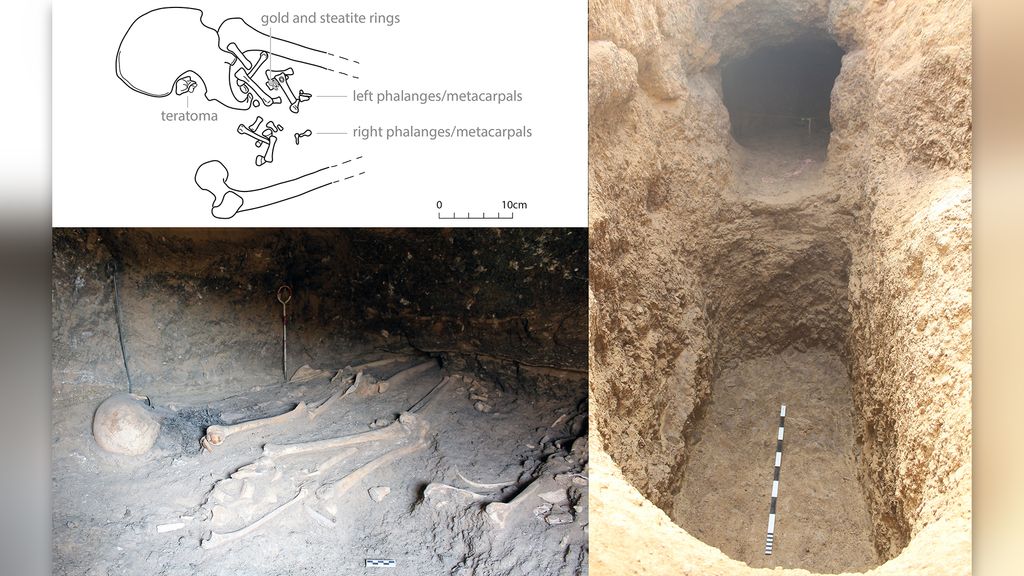

Tomb 3 of the North Desert Cemetery at Amarna, Egypt. Right: Shaft with the north chamber in the background. Bottom left: Individual 3051 on the far left. Top left: Illustration of the pelvic area of Individual 3051, showing the positions of the teratoma and finger rings. (Image credit: M. Wetzel/Amarna Project)

Only four archaeological examples of teratomas had previously been found — three in Europe and one in Peru. The recent discovery of a teratoma in the New Kingdom period cemetery in Amarna, Egypt, both founded around 1345 B.C., is only the fifth archaeological case published, making it the oldest known example of a teratoma and the first ancient case found in Africa.

Amarna was a short-lived city on the eastern bank of the Nile River, about halfway between the cities of Cairo and Luxor (ancient Thebes). It functioned as the center of pharaoh Akhenaten’s worship of the sun god Aten and was home to his royal court. Although the city included temples, palaces and other buildings that supported a population of around 20,000 to 50,000, it was abandoned within a decade after Akhenaten died in 1336 B.C., the study reported.

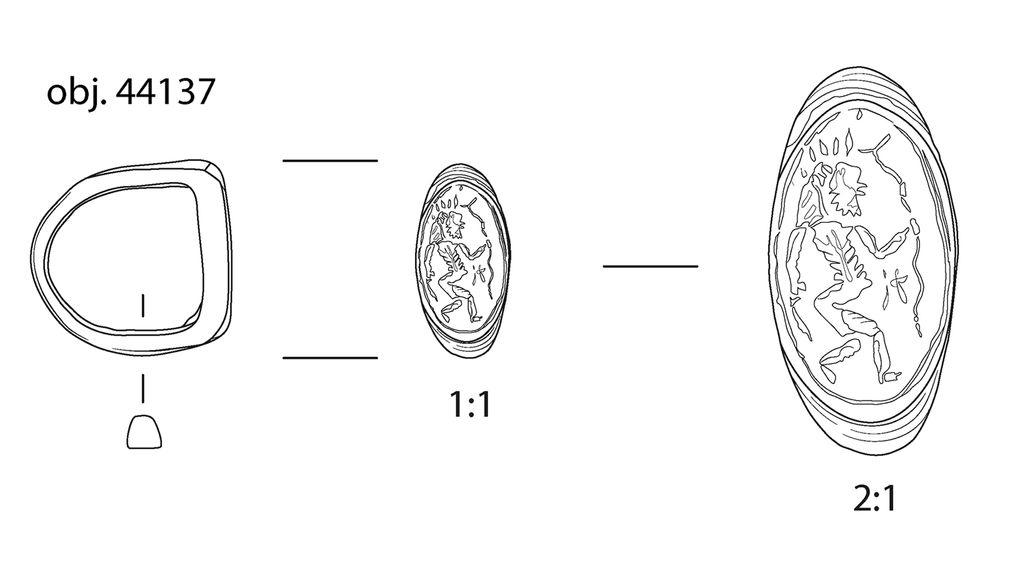

Four large cemeteries associated with Amarna have been investigated by archaeologists. In one tomb in the North Desert Cemetery that consisted of a shaft and a burial chamber, researchers found the skeleton of an 18- to 21-year-old woman wrapped in a plant fiber mat. She was buried with a number of grave goods, including a ring decorated with the figure of Bes, a deity often associated with childbirth, fertility and protection.

During excavation, archaeologists noticed something unusual in the woman’s pelvis: a bony mass, about the size of a large grape, with two depressions that contained deformed teeth.

Gretchen Dabbs, a bioarchaeologist at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, and colleagues published the discovery of this tumor online Oct. 30 in the International Journal of Paleopathology. Ruling out other diagnoses, they suggested that the presence of teeth and the location within the woman’s pelvic region indicated it was an ovarian teratoma.

The Bes ring may hint that the teratoma was symptomatic, as the possible “magico-medical” object was placed on the woman’s left hand, which was folded across her lap above the teratoma. This may mean the woman “was attempting to invoke Bes to protect her from pain or other symptoms, or aid in her attempts to conceive and birth a child,” they wrote in their study.

“By 18-21 years, this individual probably would have been someone’s wife,” Dabbs told Live Science in an email, but there is also “little doubt she was working in some fashion.” Previous research at Amarna has suggested that women this age were engaging in a range of trades, which might have included working on state-level building projects, brewing beer, or tending to household gardens and livestock.

Allison Foley, a bioarchaeologist at the College of Charleston in South Carolina who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that this discovery is important because “teratomas are very rarely identified archaeologically.” The Amarna example demonstrates how researchers can learn more about what living in ancient Egypt was like, Foley said, and the “presence, location, and possible symbolic importance of the Bes ring as a token of protection and fertility is particularly fascinating and evocative.”

Dabbs is still working on the full analysis of the hundreds of skeletons excavated last year from the North Desert Cemetery at Amarna. But future plans include looking into biological relationships among the people buried there, as well as further investigating other Egyptian burials with potential “magico-medical” objects.