The Altar Stone is a purplish-green sandstone that sits among the makeup of Stonehenge, a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain, in Wiltshire, United Kingdom. For over a century, archaeologists and scientists believed they knew where the stone came from. However, its origin has since been put into question, thanks to a recent discovery.

Lumping in the Altar Stone with Stonehenge’s ‘bluestones’

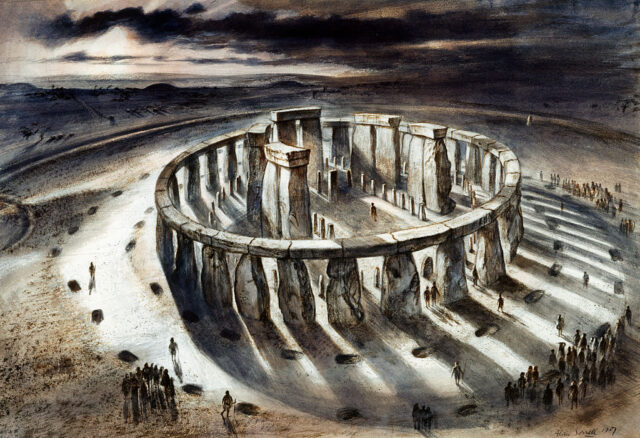

Also known as Stone 80, the Altar Stone was initially believed to have originated in the outcrops of the Senni Formation (formerly the Senni Beds) in Wales, part of the Old Red Sandstone. It’s located within the inner circle of Stonehenge, and while it once stood at over 16 feet tall, it has since sunk into the ground and been covered by two blue igneous rocks.

These rocks, known as “bluestones,” have long been thought to have come from the Mynydd Preseli area of Wales, with the Altar Stone lumped in with them. However, with the study The Stonehenge Altar Stone was probably not sourced from the Old Red Sandstone of the Anglo-Welsh Basin: Time to broaden our geographic and stratigraphic horizons?, this assumption has been thrown out the window.

Studying the Altar Stone

The study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, discusses how the team investigated the Altar Stone’s origin.

Examining 58 samples taken from the Old Red Sandstone through such techniques as portable XRF and SEM-EDS analysis and Raman Spectroscopy, only four had barium levels near the lower range of those noted in the Altar Stone’s composition. However, while they had higher barium levels, their mineralogy didn’t match, signaling to the team that we’ve likely attributed the stone’s origin to the wrong location.

“It now seems ever more likely that the Altar Stone was not derived from the [Old Red Sandstone] of the Anglo-Welsh Basin, and therefore it is time to broaden our horizons both geographically and stratigraphically into northern Britain and also to consider continental sandstones of a younger age,” the team, led by earth scientist Richard Bevins, wrote in the study.

“We therefore propose that the Altar Stone should be ‘de-classified’ as a bluestone, breaking a link to the essentially Mynydd Presli-derived bluestones.”

The bluestones the Altar Stone was initially lumped in with date back 400 million years. It’s the team’s theory that archaeologists should be looking for rock formations that are younger, between 200 and 300 million years old. As most of these are located in northern Britain, this could signal that the individuals who built Stonehenge were transporting materials a longer distance than previously believed.

Shedding light on Stonehenge’s construction

There are roughly 175 miles between Pembrokeshire, Wales and Salisbury Plain. The relation between the two places, besides distance, has long been a subject of extensive research. While the ancient world was no stranger to monolithic structures, the difference between Stonehenge and other structures lies in the choice to neglect local stones.

With a number of questions still remaining, scientists announced in February 2019 that they might be one step closer to solving this mystery. The discovery by the team, led by Mike Parker Pearson of University College London’s Institute of Archaeology, of massive stone-cutting tools in Pembrokeshire sheds new light on this complex debate.

The team claimed to have found the prehistoric tools used to quarry the original standing stones that date from the earliest phases of Stonehenge, just after the religious site adopted its monumental stone features. The tools were found on the northern slopes of the Preseli Mountains in Pembrokeshire, where two former quarries were located.

The experts used chemical analysis to track the bluestone from Stonehenge to Pembrokeshire and claim there are at least three more locations that were used to quarry stones for the sacred site.

A host of stone-cutting tools were discovered

The discovery included several hammerstones used for inserting and forcing in the wedges, which would cause the large parts of the stone to detach from the rock. The wedges were made from sandstone, and 15 of them were discovered during this particular excavation.

Apart from the tools, traces of V-shaped slots were also noted in two columns of what was once the Pembrokeshire quarry. They seem to have been fitted, but for some unknown reason were never used. It was as if the ancient stonemasons had left them there as evidence of their methods and work.

Regarding the discovery, as well as its implications, Mike Parker Pearson said in a press release, “Every other Neolithic monument in Europe was built of megaliths brought from no more than 10 miles away. We’re now looking to find out just what was so special about the Preseli hills 5,000 years ago, and whether there were any important stone circles here, built before the bluestones were moved to Stonehenge.”

Theories abound over how the stones were transported

Theories are currently being spawned as to how and why these prehistoric men were so keen to cross such a large distance while transporting stones that weighed up to four tons each. As for transport, there are two dominant options. Firstly – and perhaps the most logical – was that the stones were carried on rafts, or catamaran-like boats, along the coast and transported via the Avon to within 20 miles of Stonehenge’s location.

The second theory is presumed to be by land. The idea of transporting 79 huge pieces of stone across the country in this way must have been a very strong demonstration of might, one that could’ve symbolically consolidated a power struggle between rival tribes and clans that inhabited Britain in the third millennium BC.

In such a case, they would probably be carried by stretchers, sleds or rollers facing an unforgiving terrain. The use of rivers would be fairly limited in this case, therefore demanding tons of manpower be employed.

These two options offer a solution as to how the bluestones were transported. However, “why” is an entirely different issue.

Why were these specific stones chosen?

By analyzing the bones excavated in the vicinity of the site, the team determined that a number originated from the very area where the stones can be traced. Therefore, it’s possible that the community that built Stonehenge migrated from southwestern Wales and possibly even brought the stones with them.