Ramesses II is arguably one of the greatest pharaohs of ancient Egypt (hence named Ramesses the Great), and also one of its most well-known. Ramesses II, the third pharaoh of the 19 th Dynasty, ascended the throne of Egypt during his late teens in 1279 BC following the death of his father, Seti I. He is known to have ruled ancient Egypt for a total of 66 years, outliving many of his sons in the process – although he is believed to have fathered more than 100 children. As a result of his long and prosperous reign, Ramesses II was able to undertake numerous military campaigns against neighbouring regions, as well as build monuments to the gods, and of course, to himself.

One of the victories of Ramesses II’s reign was the Battle of Kadesh. This was a battle fought between the Egyptians, led by Ramesses II and the Hittites under Muwatalli for the control of Syria. The battle took place in the spring of the 5 th year of the reign of Ramesses II, and was caused by the defection of the Amurru from the Hittites to Egypt. This defection resulted in a Hittite attempt to bring the Amurru back into their sphere of influence. Ramesses II would have none of that and decided to protect his new vassal by marching his army north. The pharaoh’s campaign against the Hittites was also aimed at driving the Hittites, who have been causing trouble for the Egyptians since the time of the pharaoh Thutmose III, back beyond their borders.

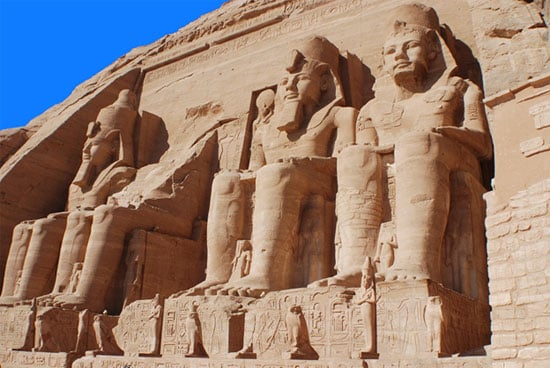

According to the Egyptian accounts, the Hittites were defeated by them, and Ramesses II had gained a great victory. The story of this victory is most famously monumentalised on the inside of the temple of Abu Simbel. In this relief, the larger than life pharaoh is shown riding on a chariot and striking down his Hittite enemies. Indeed, this image succeeds in conveying the sense of power and triumph that Ramesses II aspired to achieve. Nevertheless, according to the Hittite accounts, it seems that the Egyptian victory was not so great after all, and that it was exaggerated by Ramesses II for the purpose of propaganda. What is clear, however, is that power relations in the ancient Near East were significantly changed after this battle. The first known peace treaty was signed between the Egyptians and the Hittites, and the Hittites were recognised as one of the region’s superpowers. This treaty would also set the stage for Egyptian-Hittite relations for the next 70 years or so.

Despite being the one of the most powerful men on earth during his life, Ramesses II did not have much control over his physical remains after his death. While his mummified body was originally buried in the tomb KV7 in the Valley of the Kings, looting by grave robbers prompted the Egyptian priests to move his body to a safer resting place. The actions of these priests have rescued the mummy of Ramesses II from the looters, only to have it fall into the hands of archaeologists. In 1881, the mummy of Ramesses II, along with those of more than 50 other rulers and nobles were discovered in a secret royal cache at Dier el-Bahri. Ramesses II’s mummy was identified based on the hieroglyphics, which detailed the relocation of his mummy by the priests, on the linen covering the body of the pharaoh. About a hundred years after his mummy was discovered, archaeologists noticed the deteriorating condition of Ramesses II’s mummy and decided to fly it to Paris to be treated for a fungal infection. Interestingly, the pharaoh was issued an Egyptian passport, in which his occupation was listed as ‘King (deceased)’. Today, the mummy of this great pharaoh rests in the Cairo Museum in Egypt.