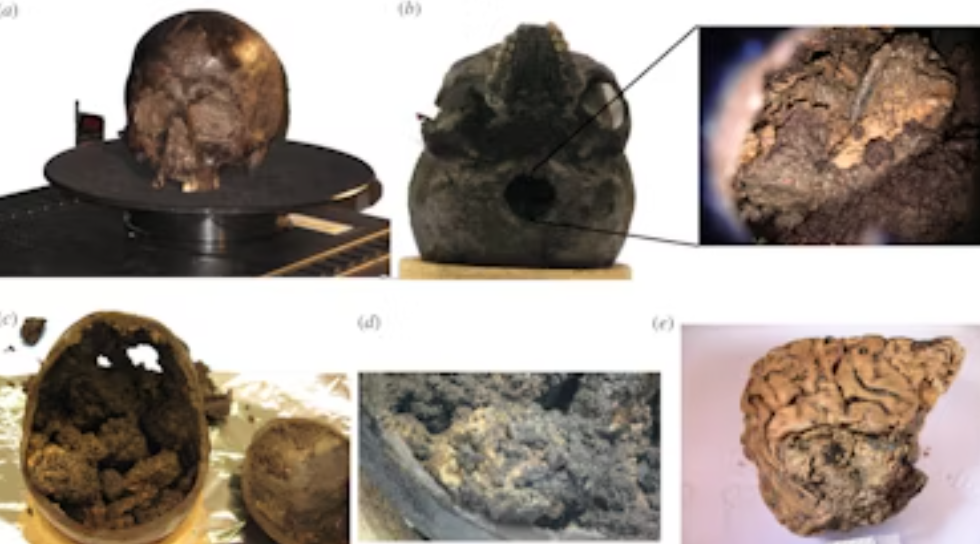

When researchers pulled a dark human skull, covered in thick mud, from a waterlogged pit in the small village of Heslington, 200 miles north of London, they did not expect to find a wonderfully-preserved brain hiding within. The brain, analysis suggested, belonged to a middle-aged man who lived sometime between the 7th century BCE and the 5th century BCE. After his death, nature conspired to keep the brain within his skull — but how this natural preservation occurred has been something of a mystery.

Researchers have discovered preserved brains and brain tissues before — including those deliberately preserved by mummification — but the Heslington brain is unique in that it is the only brain from this particular time period.

A new study, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface on Jan. 8, examined the brain at a molecular level, searching deep within the folds and crinkles for answers. Performing a range of experiments, the study identified over 800 proteins and was able to show they even retained some of their ability to generate an immune response.

Once we die, our bodies are meant to break down. Brains are particularly prone to decomposition because they have a high amount of fat. We become food for the bacteria we once housed, which move the process along. Molecules like DNA — which can tell us a lot about a particular fossil’s life — are prone to damage and break down relatively quickly, but proteins are a little more hardy. They’re becoming increasingly important markers, helping archaeologists answer long-standing questions about human history.

The brain was discovered, muddied and shrunken, inside the dark skull.

Axel Petzold

Here, the proteins tell a story about the exquisite preservation: They folded themselves up into stable “aggregates” and prevented protein degradation. Can that completely account for the preservation of the structure? It’s likely several factors contributed to the Heslington brain’s remarkable state and other hypotheses for its survival have been thrown up in the past.

First, it wasn’t deliberately preserved — there’s no signs of embalming or the like. However, earlier studies of the brain suggested the man may have been hanged and his head sliced off — with the fresh remains being deposited into the pit almost immediately. The soil, cold and low in oxygen, would have then aided the preservation, preventing bacteria from taking full advantage and feeding on the remains.

Researchers also looked to see if the specimen showed any signs of neurological disease but analysis did not demonstrate any evidence of protein buildup which would indicate the man suffered from a prion disease such as CJD or Kuru.

The researchers suggest the new findings on protein stability will benefit the fields of biomarker research, proteomics and archaeology.