During the 7 th and 6 th centuries B.C., the ancient Greek city-states began establishing colonies on the coast of the Crimean peninsula in the Black Sea. Panticapaeum, Theodosia and Kimmerikon, for instance, were founded by the Milesians, while another settlement, Nymphaion was founded by colonists from Samos. Around the 5 th century B.C., the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus was founded. Although little is known about this kingdom in the Crimea, they have left behind one of the most impressive kurgans in the region, the so-called Royal Kurgan.

Kurgans are monumental burial mounds, within which is a burial chamber. These structures were first used in the Caucasus during the 4 th millennium B.C., and subsequently spread to eastern, central and northern Europe in the following millennium. By the time the Greeks colonized the coastal area of the Crimean peninsula, kurgans had already been in use for a long time by the region’s inhabitants, the Scythians.

The Royal Kurgan can be found in the region of Kerch, which is located in the eastern part of the Crimean peninsula. Incidentally, there are about 200 other kurgans in Kerch and its surrounding area, many of which would almost certainly have pre-dated the Royal Kurgan.

During the 5 th century B.C., Kerch was the site of the Milesian colony of Panticapaeum. This area was also part of the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus when it came into being. Thus, the Royal Kurgan is said to be the final resting place of one of the Bosporan kings, most likely Leukon of Bosporus, who lived during the 4 th century B.C.

Although the exterior of the Royal Kurgan is said to be characteristically Scythian, its interior is believed to have employed Greek architectural techniques, thus demonstrating a blending of local and foreign cultures that probably happened during the time of the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus.

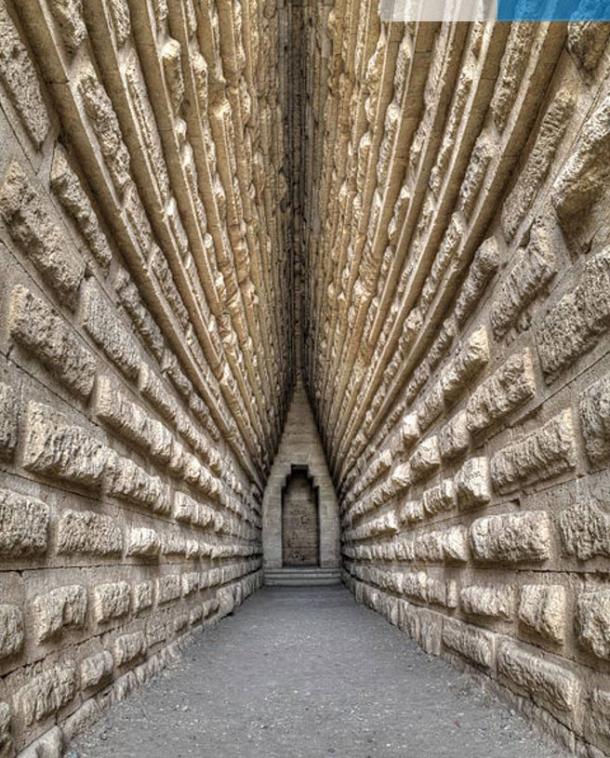

The ‘Royal Kurgan’ of Kerch, Crimea. Wikimedia Commons

The ‘Royal Kurgan’ of Kerch, Crimea. Wikimedia Commons

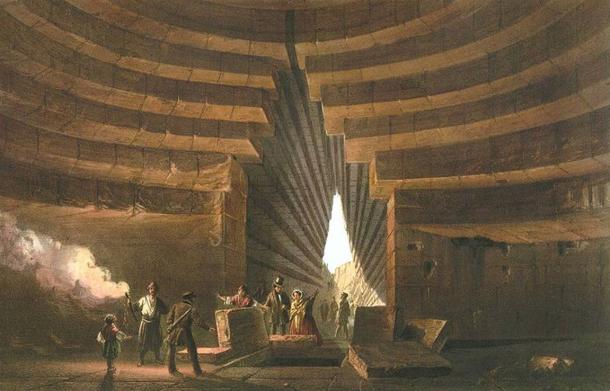

The mound of the Royal Kurgan is almost 20 meters (65 feet) in height, and the circumference of its base is roughly 250 meters (820 feet). Within the burial mound is a stone vault with a square floor plan. As the chamber rises, it merges into the circular shape of a corbelled dome, and reaches a height of almost nine meters (30 feet). The entrance of the burial chamber is formed of 11 rows of limestone slabs, and built in the corbelled vault technique. Preceding this entrance is a corridor which is around 36 meters (118 feet) long and three meters (10 feet) wide.

Between 1833 and 1837, excavations were carried out around the Royal Kurgan, and it was opened. Apart from the remains of a wooden sarcophagus, the kurgan contained little else. Hence, it has been speculated that the Royal Kurgan was looted by grave robbers, as valuable items were normally found within these structures. Interestingly, small crosses and the name ‘Kosmae’ can be found carved onto the walls of the kurgan. It has been suggested that these were left by early Christians who used the burial chamber as a place of refuge or sanctuary.

Despite the lack of archaeological and literary evidence, the claim has been made from the start that the kurgan belonged to a king. The Russian name for the Royal Kurgan is ‘Tsarsky Kurgan’. It is perhaps the massive size of the Royal Kurgan that prompted archaeologists to conclude that the kurgan was built by a king, hence naming it as such in the first place. Nevertheless, the lack of supporting evidence ought to make us question whether the kurgan was indeed the burial place of some ancient monarch. Still, it is unlikely that the Royal Kurgan would be changing its name any time soon, even if new evidence were to surface.

Detail. Painting, 1856, of one of the many kurgans, the ‘Tomb of Mithridates’ near Ketch. Public Domain