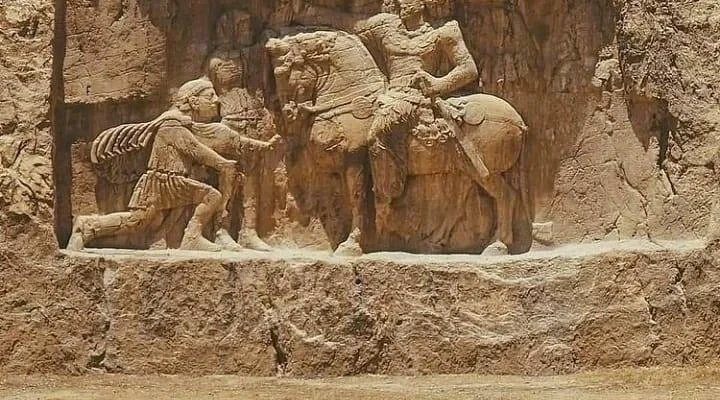

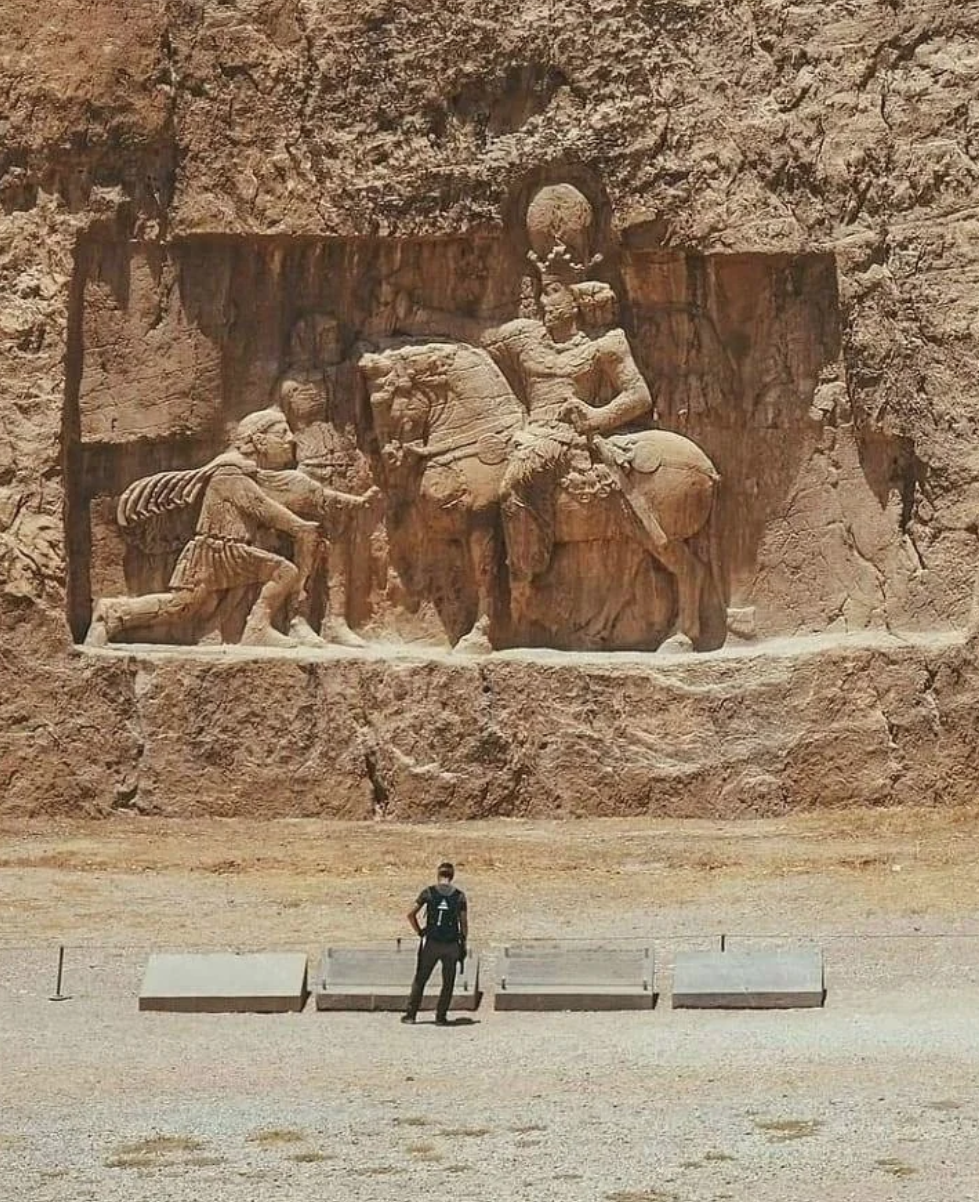

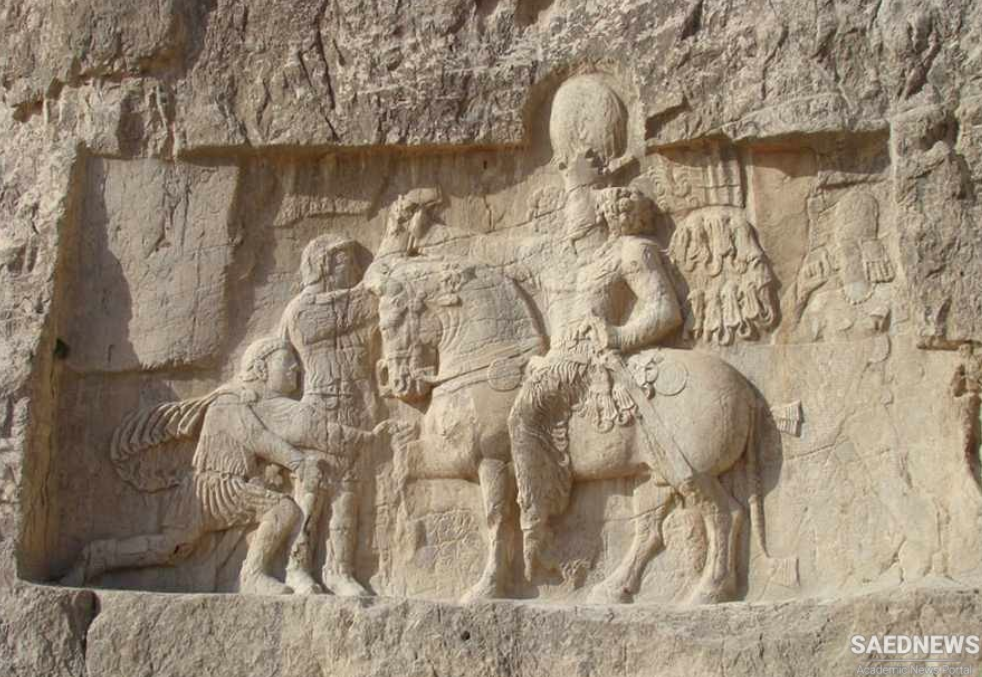

The triumph of Shapur was commemorated by rock-carvings showing him on horse-back and his Roman opponent kneeling before him at Naqsh-i Rustam and at BIshapur. Shapur’s forces again ravaged Syria and also invaded Cappadocia.

In the great inscription of Shapur I the various cities taken are listed, but they were not held for more than a short period. It was less the Romans and more Odenath, the ruler of Palmyra, who attacked detachments of the Persians causing them to retreat to their homeland. The history of the next few years is clouded, for the extent of Palmyrene successes against Shapur is unknown. We may assume that Shapur was content to rest on his laurels and to supervise the building of dams in Khuzistan and the embellishment of his capital of Bishapur by his prisoners from the Roman empire.

Probably a short time after the victory over Valerian, Shapur made some changes in his empire. In Armenia after the murder of King Khosrov and the flight of Tiridates, a certain Artavazd seems to have ruled until about 262 when Shapur appointed his own son Hormizd-Ardashlr as great king of Armenia. Another son, also called Shapur, was king of Mesene, and he had probably succeeded his uncle Mihrshah, lord of Mesene, known from Manichaean texts. A third son Varahran, or later Bahram, was king in Gilan, and a fourth son Narseh was the king of the Sakas, ruling over large territories in eastern Iran, including Sind. Several brothers of Shapur seem to have continued in the posts assigned to them by Ardashlr; one Ardashir was king of Adiabene, and another, with the same name, was king of Kirman. Amazasp, king of Georgia, was an Iranian, possibly related to the Sasanian family. Many other princes and lords appear in the notitia dignitatum at the end of the great inscription of Shapur I.

If we examine the extent of the empire as vaunted by Shapur in his inscription, it becomes clear that much of Transcaucasia was ruled by local kings subject to him, for only in Georgia and Armenia are names of Iranians given. In the east the empire extended over the “land of the Kushans up to Pashkibur (Peshawar?), and to Kashghar, Sogdiana and Tashkent” (Parthian line 2, Greek line 4). In other words, the empire included the domain of the Kushans, at least as far as the lowlands of the north-west frontier of Pakistan. It also extended to Sogdiana and Central Asia, but did not include them. For it is likely that what Shapur meant in his inscription was that the Kushan kingdom had submitted to him, and the boundaries of that kingdom extended to Peshawar, Sogdiana, Kashghar (or possibly Kish) and Tashkent. No Sasanian prince is designated as Kushanshah by Shapur, so we may infer that the ruler who had submitted retained his title, but under Sasanian suzerainty.

At the time of the capture of Valerian, Shapur must have been advanced in age, which may explain his apparent lack of reaction to the expansion of Palmyra. The king of kings must have been busy with internal matters, for we know he took an interest in Man! and in matters of culture and thought. He built a new city in Fars province, Bishapur, where presumably artisans from the Roman empire worked, as evidenced by mosaics found there. The religious developments during Shapur’s reign are discussed elsewhere.