The ancient Egyptian pyramids have stood for thousands of years and are among the world’s most enduring monuments. But what did the pyramids look like when they were first built?

The Egyptian pyramids erupting from the sands at Giza are a testament to human ingenuity and engineering. Raised to mark the tombs of ancient pharaohs, these great structures have stood for thousands of years.

But over the millennia, the pyramids have changed, largely due to construction workers’ repurposing of in-demand materials and looting. So what did the pyramids look like when they were built?

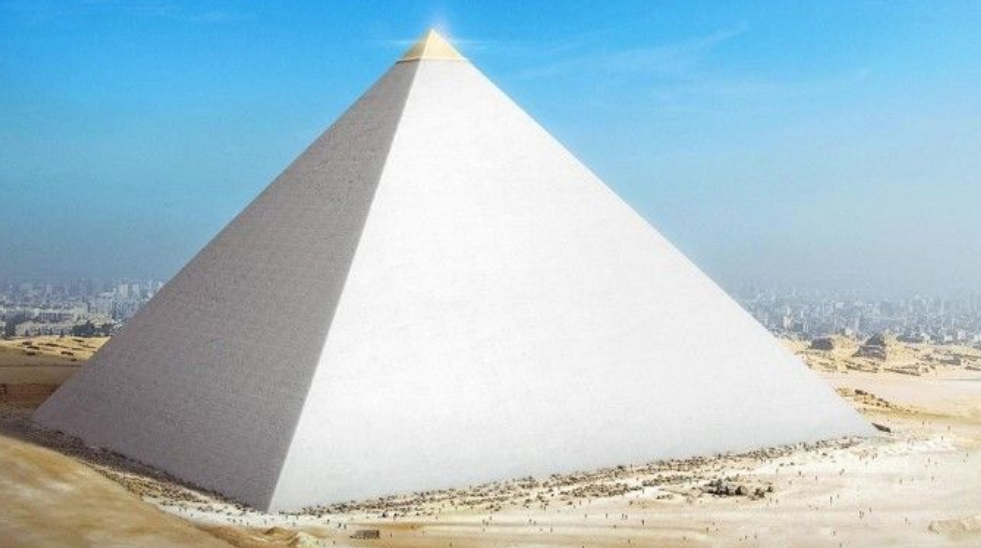

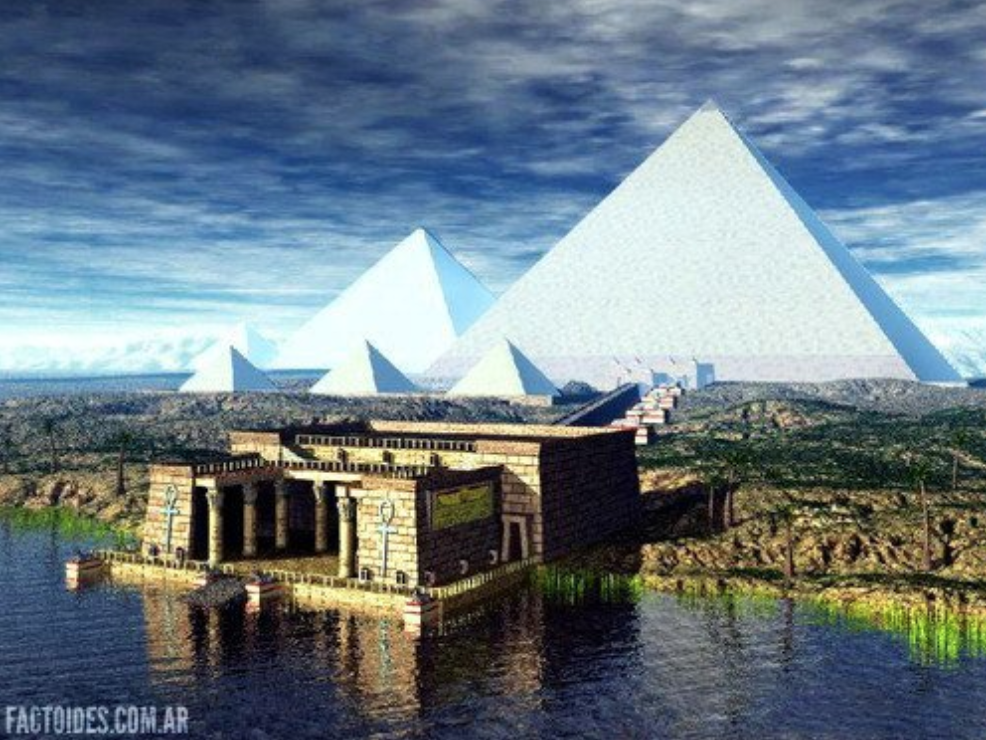

When the ancient Egyptian pyramids were originally erected, both in Giza and elsewhere, they didn’t look sandy brown as they often do today; rather, they were covered in a layer of shiny sedimentary rock.

“All the pyramids were cased with fine, white limestone,” Mohamed Megahed, an assistant professor at the Czech Institute of Egyptology at Charles University in Prague, told Live Science. The limestone casing would have given the pyramids a smooth, polished layer that shined bright white under the Egyptian sun.

Builders used around 6.1 million tons (5.5 million metric tons) of limestone during the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza alone, according to National Museums Scotland, which displays one of the original limestone blocks. The Great Pyramid — also called Khufu’s Pyramid after the pharaoh Khufu, who commissioned it during his reign (circa 2551 B.C. to 2528 B.C.) — is the largest and oldest of all the standing pyramids in Giza. However, its casing stones were later repurposed for other building work under Egyptian rulers, as was the case for most pyramid shells.

There’s evidence that the casing stones began being stripped under Tutankhamun’s reign (circa 1336 B.C. to 1327 B.C.), and this continued until the 12th Century A.D., Egyptologist Mark Lehner explained in a PBS NOVA Q&A thread. An earthquake in A.D. 1303 would also have loosened some of the stones, according to BBC News.

Today, the Giza pyramids still retain some of their original limestone casing, though it looks slightly more weathered than in ancient times. “You can see it on the top of the Pyramid of Khafre in Giza,” Megahed said.

The Pyramid of Khafre, named after the pharaoh Khafre (who reigned circa 2520 B.C. to 2494 B.C.), has casing stones leftover around its peak that give the impression that a second peak is wedged on top of the first. In ancient Egypt, this pyramid also had red granite casing around its lower levels, Egyptologist Miroslav Verner wrote in his book “The Pyramids: The Archaeology and History of Egypt’s Iconic Monuments” (The American University in Cairo Press, 2021). The third and smallest of the three main pyramids in Giza, the Pyramid of Menkaure — named after the pharaoh Menkaure, who reigned circa 2490 B.C. to 2472 B.C. — also sported red granite casing around its lower echelons.

There’s nothing at the top of the Giza pyramids today, but originally they hosted capstones — also called pyramidions — covered in electrum, a mix of gold and silver, according to Megahed. The pyramidions would have looked like pointy jewels at the tips of the pyramids.

Most pyramidions have been lost over time, but there are a few surviving examples in museums. These specimens reveal that pyramidions were carved with religious imagery. For example, the British Museum has a limestone pyramidion covered in hieroglyphics from Abydos, an archaeological site in Egypt, that depict deceased people worshipping the ancient Egyptian god Osiris and undergoing mummification from the jackal-headed Anubis.

Considering the pyramids’ former splendor, absent features today can appear like open wounds. Perhaps the best example of this is evident on the Pyramid of Menkaure. “When you see the Menkaure’s pyramid from the north, you can see a great gash, like a big depression,” Yukinori Kawae, an archaeologist at Nagoya University’s Institute for Advanced Research in Japan, told Live Science.

The Pyramid of Menkaure’s gash may be a visual blight that wouldn’t have existed in ancient times, but the benefit of such damage is that today, it provides a window into the pyramids.

“This is also the important area for archaeologists because we can see the internal structures of the pyramids,” Kawae said.